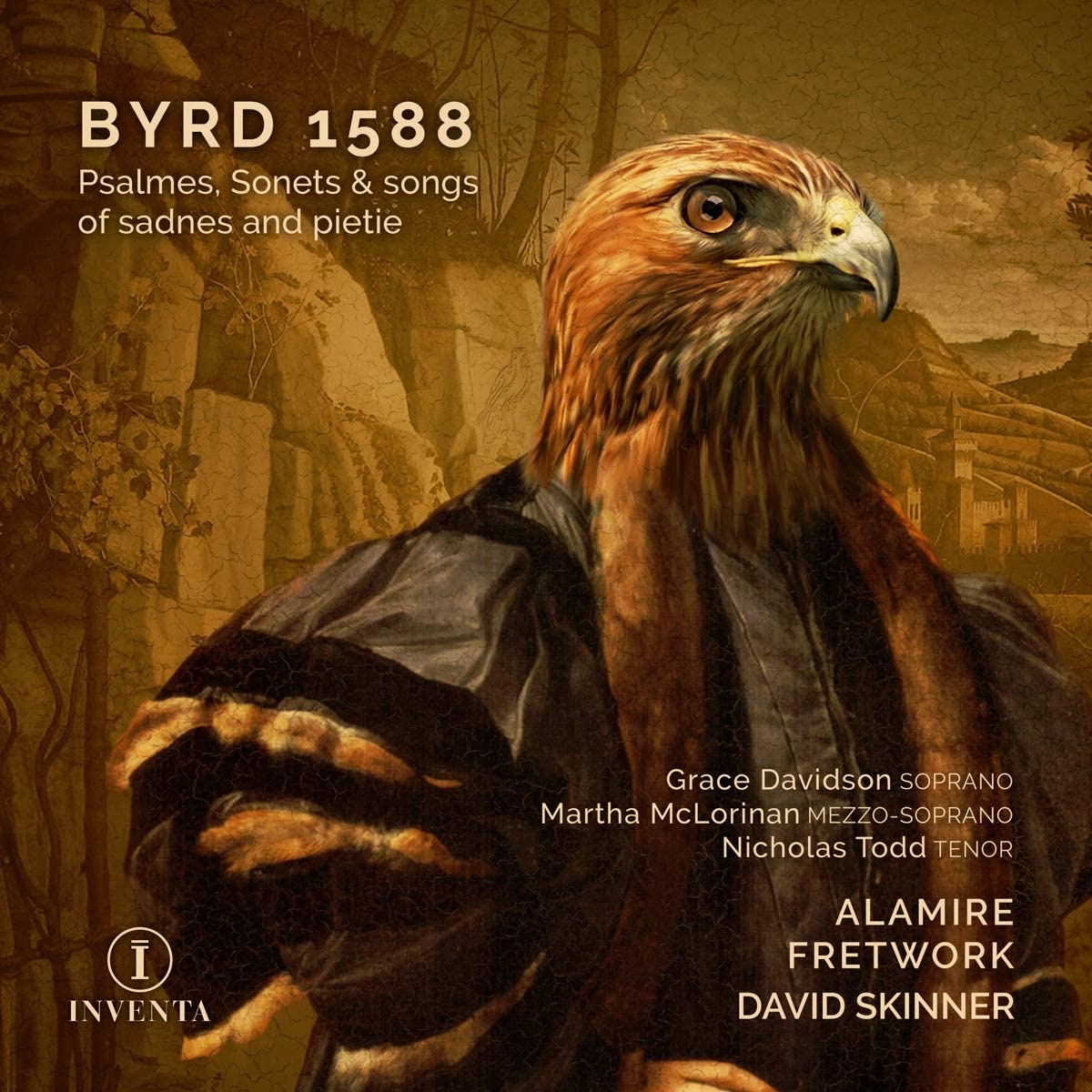

Psalmes, Sonets & songs of sadnes and pietie

Grace Davidson soprano, Martha McLorinan mezzo-soprano, Nicholas Todd tenor, Alamire, Fretwork, David Skinner

157:14 (2 CDs in a single jewel case)

Inventa INV1006

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[These sponsored links help the site remain alive and FREE!]

It is a pleasure to report that everything about this double album is excellent. The music, the concept, the soloists, the ensembles and the recording quality are all outstanding. Byrd simply does not “do” duff, and some of these works are masterpieces even by his standards. The album consists of the whole of Byrd’s first collection of songs, published to provide accurate versions to counter those that had begun to circulate in copies unsatisfactory to the composer. Many were initially composed for a single voice with an accompaniment for four instruments: unspecified, but contemporary evidence confirms viols. Here they are all arranged for five voices, though single parts in several of the songs are labelled “the first singing part”. There are also a number of these songs which survive in their original versions for a soloist with four viols (also arrangements for lute, for which Byrd never composed) in contemporary manuscripts. Just one piece, La verginella, lacks the label for a first singing part in the print but survives as an accompanied solo song in manuscript. There is also a phrase in Byrd’s introduction which can be interpreted as allowing for performances of the songs solely by instruments. Of the 35 songs, fourteen are sung by Alamire, seventeen are sung by one of the soloists accompanied by Fretwork, and four are played by Fretwork alone.

Eight of the songs are new to disc: Although the heathen poets, As I beheld I saw a herdman wild, Even from the depth, Help Lord for wasted are those men, If that a sinner’s sighs, Mine eyes with fervency of sprite, O Lord who in thy sacred tent and Where fancy fond. (Even I had never before heard If that a sinner’s sighs which is one of the four allotted here to Fretwork alone.) It is astonishing that these had not previously received commercial recordings, all being up to Byrd’s usual standard. This neglect can partly be explained by a preoccupation with a handful of other pieces from the collection, notably Lullaby (35 recordings currently available), Though Amaryllis dance in green (sixteen) and Come to me grief for ever (thirteen), plus others in high single figures. Tempting as it is to comment on all these hitherto unrecorded pieces individually and in detail, suffice it to mention a few. Even from the depth is a sonorous psalm well worthy of starting the second disc complementing O God give ear with which the album begins. Two others are perhaps the strangest items in the collection. Although the heathen poets lasts barely a minute and is anyway made of one phrase repeated. That said, it makes an impression which is out of all proportion to its brevity. Provoking even more thought is As I beheld I saw a herdman wild which, while certainly describing a destructive act of amorous despair, sounds almost hallucinatory, as Byrd gets inside the mind of the distraught rustic. Typically of the greatest composers and writers, Byrd creates a profoundly democratic work, crediting an ostensibly primitive person with profound feelings without in any way patronising, demeaning or deriding him.

Several of the songs already recorded exist in versions alternative to those selected by David Skinner, rendering Alamire’s renditions all the more welcome for comparison and variety. This is best illustrated by what is arguably the greatest song in the collection, the concluding lament for Sir Philip Sidney O that most rare breast sung here with controlled intensity by the mezzo Martha McLorinan. There are, or have been, four other recordings of this masterpiece (and should be at least four times that number). One is sung by five voices, the others by a soloist with viols etc. My “etc.” is loaded, because, well though Robin Blaze sings on his version, as a matter of personal taste and preference I cannot abide the distracting presence of Erica Clapton, aka the estimable Elizabeth Kenny and her lute plucking alongside the viols in the accompaniment. Emma Kirkby gives as fine a performance as one would expect, with Fretwork, on William Byrd: Consort Songs (Harmonia Mundi HMU 907 383). Even outshining these two distinguished ladies is the soprano Annabella Tysall with the Rose Consort of Viols on the – for now – frustratingly unavailable Ah, Dear Heart … Songs, Dances and Laments from the Age of Elizabeth I (Woodmansterne 002-2). She manages to impart the sombre text radiantly, while the accompaniment is crystal clear in every detail, each note being so important in any work by Byrd. Finally, among the solo versions, possibly even capping this wonderful recording, is the version by the countertenor John York Skinner on a disc of selections from this very collection, performed by The Consort of Musicke under Anthony Rooley (Decca 4750492). It is a cliché to refer to the otherworldliness of this voice, but not all stereotypes are always wrong, and this quality, besides Skinner’s engagement with the words, his accuracy in tuning, the steady tread as of a funeral march, and the immaculately clear accompaniment of the Consort’s viols, make this a claimant to be the finest recording of this exceptional piece. But … we are not finished yet: there is the version by five singers which I mentioned. This is by the Trinity Consort led by Clare Wilkinson (Beulah 1RF2) and in every way it complements the Decca recording which I have just mentioned, the pacing, tuning and interpretation immaculate and profoundly moving. All of Byrd’s songs, and this one, in particular, deserve nothing less.

So this present recording is a triumph. The music itself is from the top drawer. Do not be surprised if, after you will have listened to it a couple of times, you wake up of a morning and find any one of several songs running through your head. “Catchy” might not be a word that instantly springs to mind apropos of Byrd, but it is part of the success of many of these songs, and I am not sure that the old fellow would have minded the word too much. Of the more cerebral songs, the metrically sophisticated The match that’s made is memorably performed by five voices which, besides being executed superbly, is a great relief after the fussy hybrid version on the disc of 1588 selections mentioned above. On this complete recording, there are simply no duff tracks, and there is something for everybody, for every mood. The three soloists acquit themselves admirably. If I have a criticism it is that occasionally Fretwork’s inner parts are too modest or understated: the consecutive sixth with the voice in the final cadence of O that most rare breast is almost inaudible, likewise Byrd’s crucial consecutive thirds under the soloist’s first “heavy” and a few spicey passing notes in other pieces. Also, the two verses accompanied pizzicato sound twee. That said, I have never heard the dissonances delivered so deliciously in the conclusions to the burden of Lullaby and at the first “if such on Earth were found” towards the end of Why do I use my paper, ink and pen, while the accompaniments to Who likes to love and most especially the premiere Where fancy fond are bracing, buoyant and effervescent. Indeed, the latter, sung enchantingly by Grace Davidson, epitomises the excellence of this double album, a discographical benchmark.

Richard Turbet