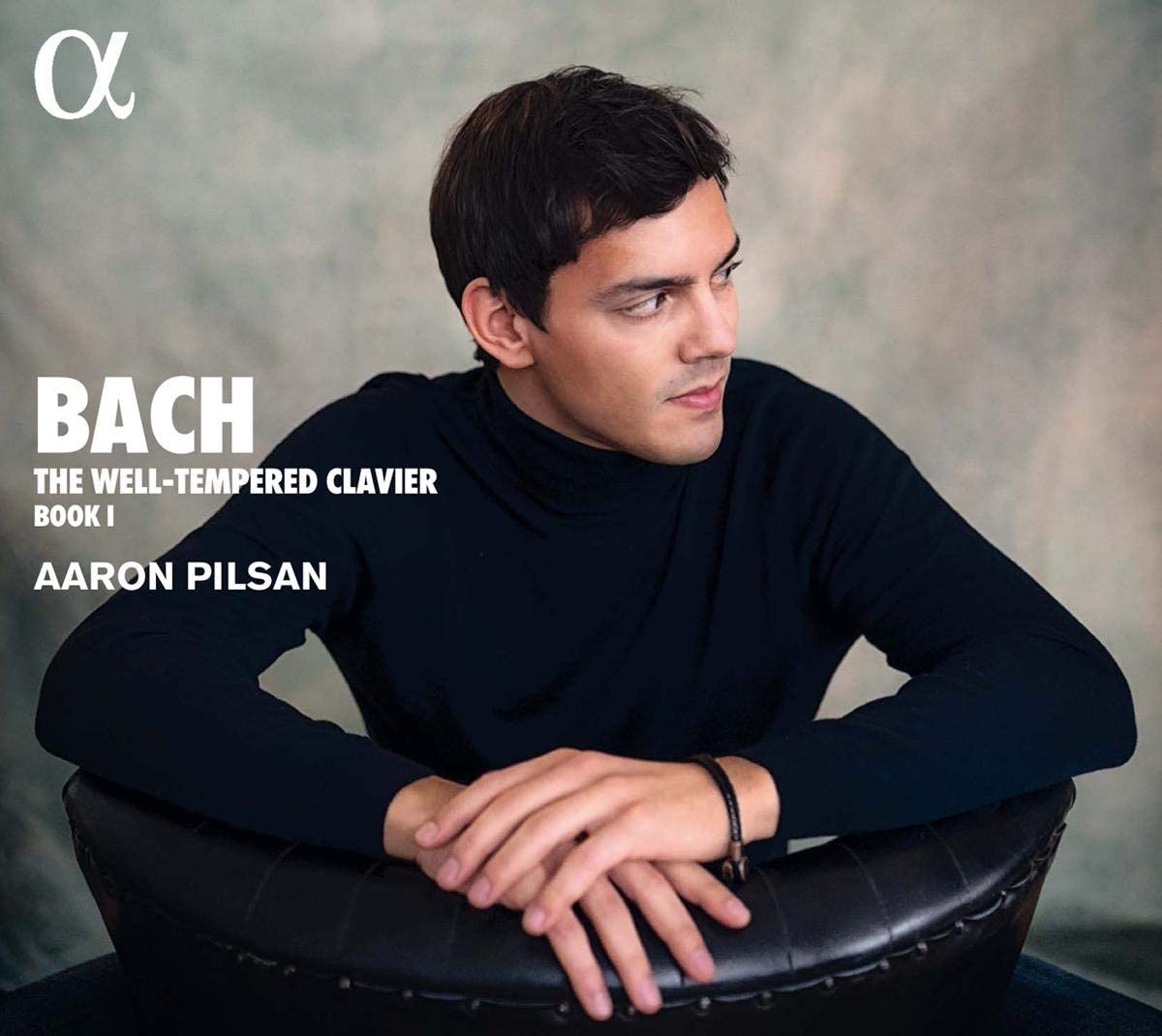

Aaron Pilsan piano

106:58 (2 CDs in a card triptych)

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[These sponsored links help the site remain alive and FREE!]

Aaron Pilsan’s complete account of Book 1 of Bach’s Well-tempered Clavier on a modern grand piano is beautifully poised and measured, with a fine sense of period. I am extremely ambivalent about Bach on the modern piano – great music like this works so well on a range of media that it seems mean to rule it out as repertoire for pianists. There is a further complication with the more abstract music of Bach, which in any case seems to transcend the instruments of his time – in the case of collections like the Art of Fugue it is not even clear that the composer had a specific medium in mind, or even that this was music intended for performance at all. So am I just being churlish in my reaction to these very fine piano performances? My main reservations are the things which a piano can do which no keyboard instrument could that the conservative J. S. Bach advocated when he conceived this collection; namely, constantly raising and lowering the dynamic levels in response to individual phrases, and bringing out certain melodic threads in the polyphonic texture. In a harpsichord or organ performance, these are things which the listener has to do for him|herself – on the piano, the performer takes these decisions for you. Even with a very fine player like Pilsan, whose clear, crisp playing reveals a deep understanding of the Baroque idiom, dynamic decisions are being taken all the time, transforming the music from anything Bach could have conceived of into something entirely different. It may be something equally engaging, perhaps more engaging for some listeners, but for me Bach makes clear in his title the medium he had in mind. For those more broad-minded than I am, these Alpha recordings with their crystal clarity and Aaron Pilsan’s carefully considered and impeccably executed performances will be very attractive.

D. James Ross