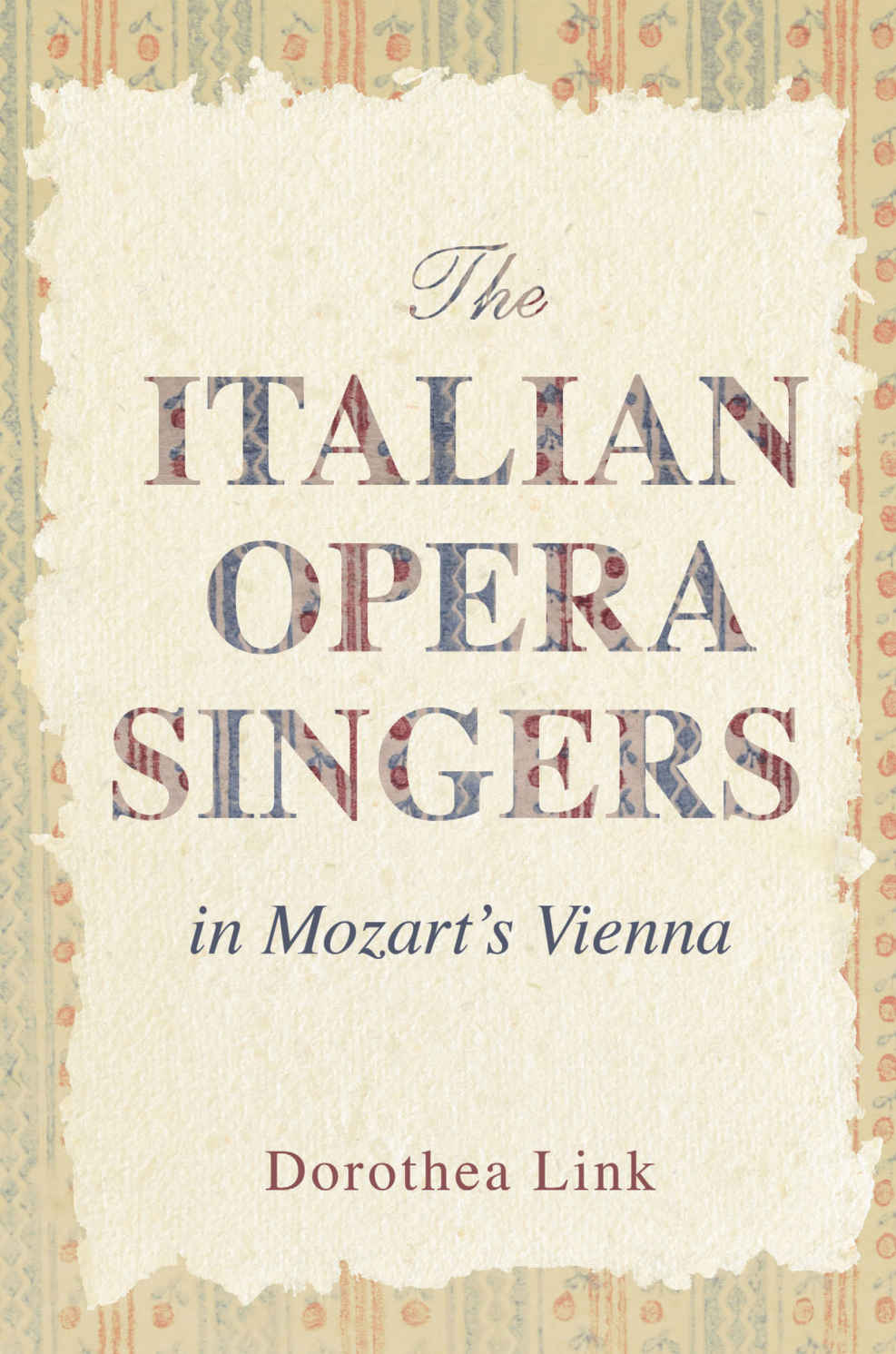

University of Illinois Press, 472 pp.

ISBN 9780252044649 (cloth) – £112:00; ISBN 9780252053658 (ebook) – £32.38 on Kindle.

The story of the Italian opera company formed in Vienna by the Emperor Joseph II might have remained an interesting byway in the history of opera but for one rather significant fact. It happened to be the birthplace of two of the three operas Mozart composed in collaboration with the court poet Lorenzo Da Ponte, all three operas of course standing among the supreme achievements of the genre. Both Le nozze di Figaro and Così fan tutte were commissions for Vienna, though the libretto of the latter only came to Mozart after Antonio Salieri, the court Kapellmeister, had declared it unworthy of being set. Don Giovanni was not a Viennese opera, having been composed for Prague in 1787, but it transferred to Vienna with a few changes the following year.

Josephine opera starts in 1783, two years after Mozart took up permanent residence in Vienna, and concludes when it was transformed in 1791, shortly after the emperor’s death the previous year. One of the remarkable aspects is that the company was run as a commercial enterprise by Joseph, who oversaw every aspect of its functioning – including the hiring (and firing) of the contracted singers, the majority of whom were Italian – over most of the course of the company’s existence. Only at the end of the period, when he was away fighting another of the endless wars with the Turks, did Joseph loosen his grip. Many of those contracted were among the leading singers of the day, a highly important asset since the success or otherwise of an opera most likely depended not so much on the composer or work but the singers, above all the prima donna (or leading lady).

It is this milieu that is thoroughly investigated in The Italian Opera Singers in Mozart’s Vienna by Dorothea Link, Emeritus Professor at the University of Georgia. As the name suggests her principal topic is the careers of the Italian singers that were engaged in Vienna; one of the most valuable sections of the book is an appendix in which the roles taken by the most significant of these singers not just in Vienna but in other major centres are charted. This in itself leads to some fascinating information that will not only be of great value to scholars but of interest to a more general readership. Who, for example, will not find questions coming to mind about the type of singer that created the well-known roles in Mozart’s Da Ponte operas when we discover the first Contessa in Figaro, Luisa Laschi was also the first Viennese Zerlina in Don Giovanni. Few today would think of casting a Zerlina as the Countess, at least not until she’d matured a bit. And who will argue with Link, having seen her argument that the role of Despina in Così is intended for a mezzo, not the soprano we generally hear? Link’s plan has been to treat each season as a separate chapter in which the comings and goings of contracted singers are recorded along with local reaction to them, leaning heavily on the formidable Count Karl Zinzendorf, a government officer and diarist, who attended virtually every opera, sometimes on multiple occasions. Zinzendorf was something of a ‘groupie’ follower of Nancy Storace, creator of the role of Susanna in Figaro, and the prima donna that dominates the earlier chapters (she was at the Burgtheater, the Viennese home of Italian opera, from 1783 to 1787. Incidentally, it is also fascinating to learn that had Figaro been premiered a few months earlier Storace would have sung the Countess, since the role of Susanna would have been sung by Storace’s co-prima-donna Celeste Coltellini had the latter not left for Naples earlier in the year. More food for thought, given that the high-spirited Storace is often thought of as the archetypal Susanna.

The question of identifying the voice types that created the familiar roles in Mozart’s operas of this period is arguably the most valuable single topic in the book, since of course it plays a part in how we view these characters when we go to these operas today, not to mention how we identify with the manner in which in the role is played or produced. A good example is Francesco Benucci (c.1745-1824), the creator of Figaro and Guglielmo (Così), and of Leporello in the Viennese Don Giovanni. Described as a buffo caricato, a complex vocal identification applied to baritones or basses, we know from the Irish tenor Michael Kelly (the first Don Basilio) that Mozart greatly admired Benucci’s singing, but it is extracts from several reviews quoted by Link that should set the Mozart enthusiast pondering: ‘Benucci combines unaffected, excellent acting with an exceptional round, full and beautiful voice… He has a rare habit that few Italians share: he never exaggerates. Even when he brings his acting to the highest extremes, he maintains propriety and secure limits, which hold him back from absurd, vulgar comedy’. Another report speaks of his ‘inimitable polish and comic naturalness’ and his ability to convey, ‘the ridiculous with decorum in every, in every word, in every gesture, in every look, in every movement …’ These are words that should set modern directors, singers and audiences thinking about the way in which we play these – and other comic bass characters – today.

There is so much valuable detail of this kind in these pages that in that sense the book is self-recommending to anyone that would better understand the opera of the period, and not just in Vienna. Regrettably, for the general reader, the book is written in an academic style that makes it difficult to read and will likely restrict it to being a reference tool. Link’s prose lacks style, but above all she has a tendency to incorporate long lists of facts that would have been far better put into tabulated form, leaving her prose to flow more naturally. There are also a number of typographical errors and several instances of carelessness, such as that on p 312, where we are told a proposal to invite Francesco Bussoni, the creator of the role of Don Alfonso (Così) to sing ‘Haydn’s oratorio was rejected …’ Which Haydn oratorio is not identified (it was Il ritorno di Tobia).

Such caveats do not detract from the academic achievement of The Italian Opera Singers, which is considerable and laudable. The book is an important addition to our knowledge and understanding of opera in Mozart’s Vienna, not just the operas of Mozart himself, but of many other composers such as Salieri, with the focus very much on those that performed them.

Brian Robins