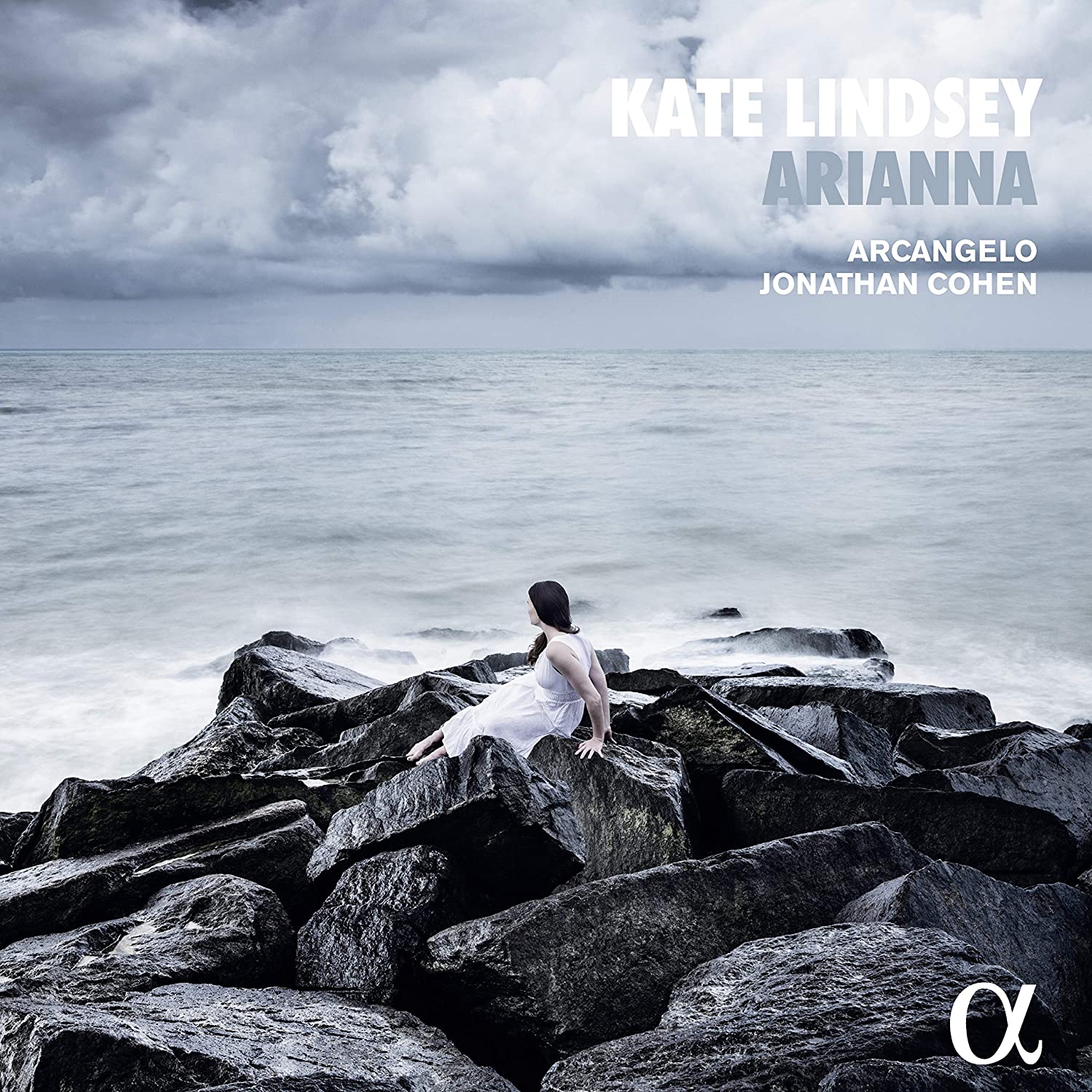

Kate Lindsay, Arcangelo, Jonathan Cohen

72:13

Alpha Classics Alpha 576

Handel: Ah! crudel, nel pianto mio; Haydn: Arianna a Naxos; A. Scarlatti: L’Arianna

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Arianna, or Ariadne, is the archetypal classical femina abandonata –according to Hesiod, having sacrificed everything to accompany the hero Theseus, she is subsequently abandoned (can I get amen, sisters?) on Naxos, only to be ‘rescued’ by Bacchus. The secular Baroque cantata relied on the musical display of extremes of emotion, and Ariadne’s tragic story seemed ideal and was the subject of many such pieces – composers continued to be drawn to the legend, up to and including Richard Strauss. Kate Lindsey and Arcangelo have selected two such cantatas by Alessandro Scarlatti and Haydn – a third piece by Handel features a non-specific heroine in the Ariadne mold. Scarlatti’s L’Arianna from 1707 sets the standard, with a sequence of movements exploring Ariadne’s changing emotions, covering the whole gamut from melancholy to murderous rage. Mezzo-soprano Kate Lindsey is more than a match for the demands of this rapidly changing scenario, with a blistering account of “Ingoiatelo, lacerato” inciting the ocean to consume the treacherous Theseus and a deeply touching reading of “Struggite, o core”, where our heroine subsumes her audience into her own grief. The anonymous poet cleverly frames Ariadne’s story with narrative, so we conclude with a recitativo arioso imparting the happy ending. For Handel’s Ariadne-esque cantata Ah! Crudel, nel pianto mio, again of around 1707 when the composer was in his early twenties and resident in Rome, he chooses to feature an obbligato solo oboe (with a second in the orchestra) to cleverly and plangently enhance the suffering of his heroine. As in the Scarlatti, Lindsey’s expressive singing is beautifully supported by wonderfully sympathetic playing from Arcangelo. This Handel piece is relatively well known and probably the composer’s most prominent masterpiece until the appearance of Agrippina a couple of years later. It is fascinating to hear how times have changed in Haydn’s approach to the legend – oboes are replaced by clarinets and flutes and the whole mood is of classical restraint as opposed to Baroque excess. Lindsey is the mistress of this idiom too, while Arcangelo make the step into classical mode seem effortless. The piece dates from 1789, and while Haydn fully intended to orchestrate it, it fell to his pupil Neukomm to fulfil his master’s intentions in a delightfully colourful realisation.

D. James Ross