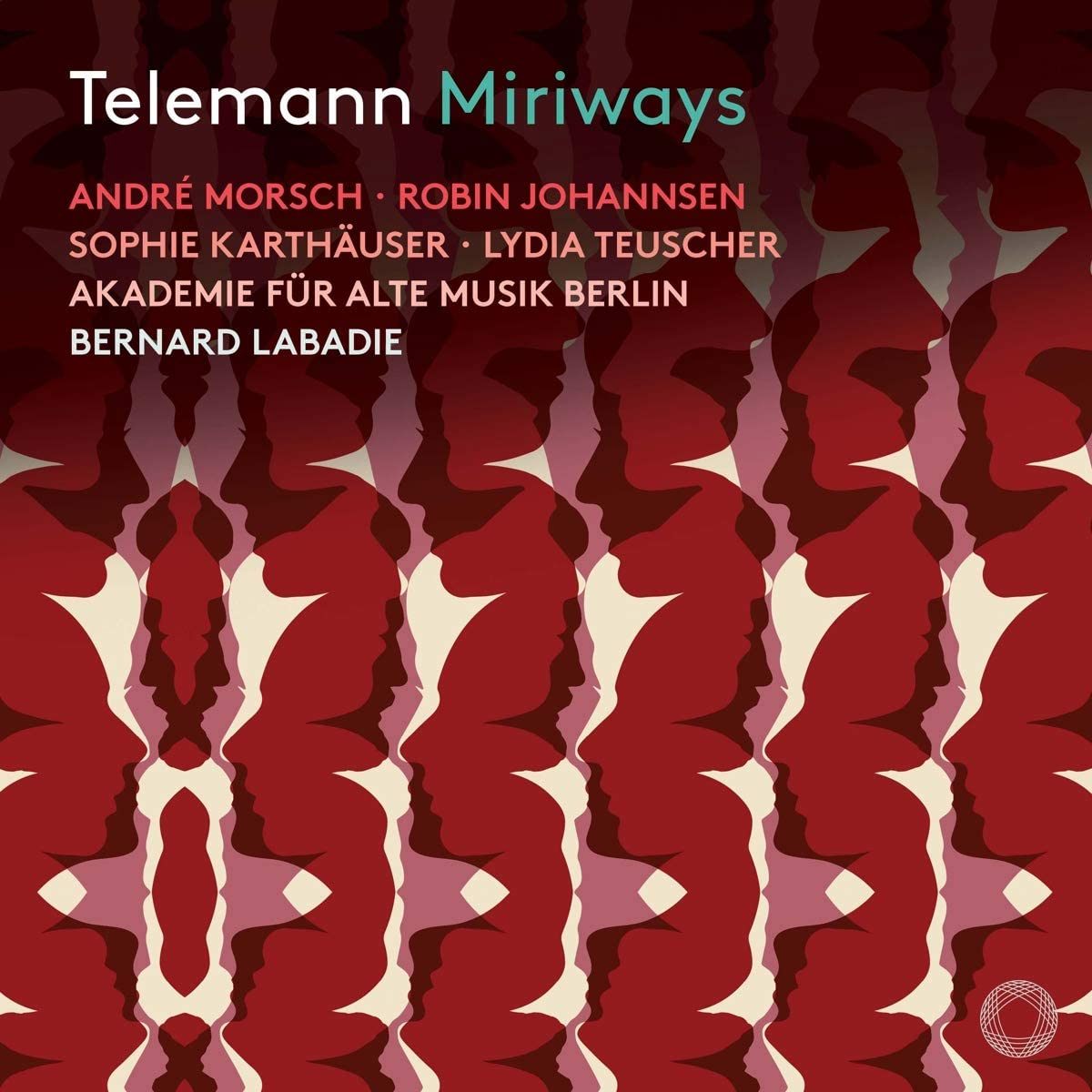

André Morsch Miriways, Robin Johanssen Sophi, Sophie Karthäuser Bemira, Lydia Teuscher Nisibis, [Michael Nagy Murzah, Marie-Claude Chappuis Samischa, Anner Fritsch Zemir, Dominik Köninger Geist/Scandor, Paul McNamara Gesandter,] Academie für Alte Musik Berlin, Bernard Labadie

150:23 (2 CDs)

Pentatone PTC 5186 842

Click HERE to buy this from amazon.co.uk

There has been some serious attention given to this splendidy exotic baroque opera from the lively Hamburg stage, which premiered on the 26th May 1728, that was six years after Telemann took full control of the Gänsemarkt Opera house, and ten years before it finally failed to draw in the crowds and faltered to a close in 1738. This places this remarkable gem of a libretto by Johann Samuel Mueller, later to become principal of Hamburg’s famous Johanneum school, in the years of the opera’s artistic ascendancy. As the historical background goes, “Miriways” or more correctly Mir Wais, an Afghan tribal warlord (or possibly his son) was the instigator of several uprisings, setting in motion the liberation of Kandahar province from Persian rule circa 1700. Now place the main character within this historic frame but add his missing daughter, Sophi, who loves the deposed Shah’s son, who Miriways guides to pick a wife, and he falls (luckily!) for Bemira the reputed daughter of Nisibis, a beautiful woman fled from Ispaphan, who attracts the attention of a tartar* and Persian prince (Zemir) and now we have several love interests and episodes of misplaced, thwarted and unrequited love(s) swaying and sighing through the plot.

There are some really quite exquisitely well-observed arias from the main love-entangled protagonists and even some excellent martial ones for Miriways himself: Ein doppler Kranz (Track 7) is a striking example. The opening ouverture with prominent horns sets out in fine form with an animated majestic tone; in fact, the horns come to the fore on several notable occasions, giving at times hints of exotic foreign tones, but also marking intense emotions of the main “dramatis personae” bearing their souls. Telemann deftly deploys the rich array of instrumentation to marvellous effect, from the delightful dulcet sleep scene from Nisibis (Track 13) and the pleasant rising wind for *Murzah’s aria (Track 15), also the incredibly vivid outbreak of fire in Act 3 scene 6, after the simply wonderful drinking Aria from Scandor, a servant of Samisha, Miriways’ secret wife, mother of Bemira (here followed by an outbreak of spontaneous applause!) all illustrating the clever contrasts and tremendously well-contoured dramatisation of the piece.

This very fine live recording by NDR in 2017 has a few differences to the 2014 CPO recording (777 752-2) by Michi Gaigg and L’Orfeo Barockorchester, which itself has some instrumental insertions from TWV50:4, and is a very noteworthy, clean and tidy version with many admirable qualities; this said, hand on heart, the nimble, alert Akamus Live version here, seems to shine and shimmer with that added “something” that draws you along, right through the love-entanglements, right up to the hopeful (anticipated) “happy end”/ final denouement.

Amid the quivering, fluttering pairs of flutes, and oboes/oboi d’amore, it is probably the strident pair of horns which leave a lasting impression. To think that this was but one of at least three operas Telemann produced in 1728! Only one other has survived and it still awaits resuscitation from dusty slumber and neglect…

David Bellinger

The 42-Page CD booklet explains the full background to the opera, and the love entanglements (pp. 20-21)

For information: The first concert performance in modern times was given in 1992, during the 11th Telemann Festival in Magdeburg, with Musica Antiqua Köln under Reinhard Goebel. It featured a few extra arias, including one in Italian! This might possibly have been inserted when the opera was reprised in 1730 or maybe an earlier undocumented performance.