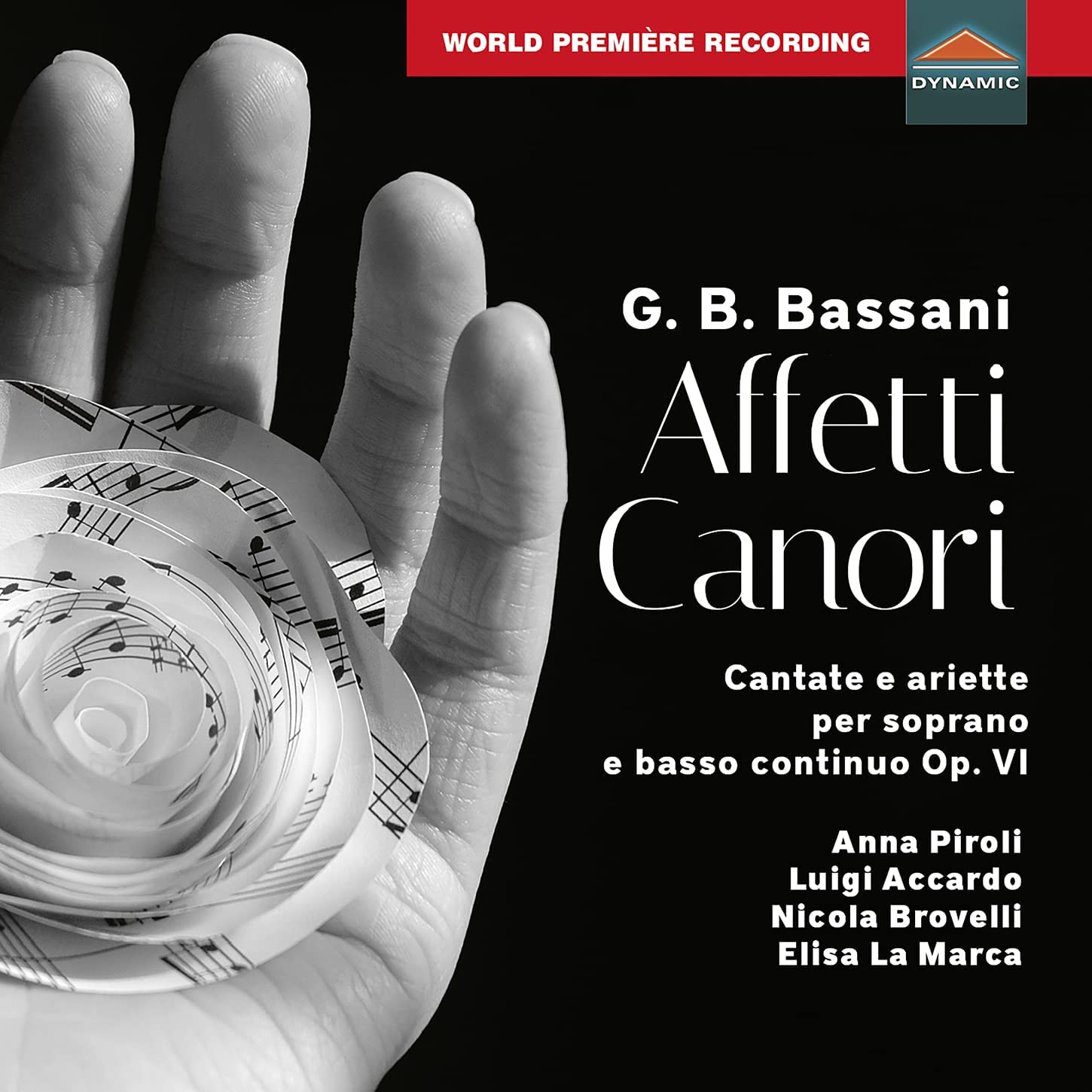

Cantate e ariette per soprano e basso continuo Op. VI

Anna Piroli soprano, Luigi Accardo harpsichord/organ, Nicola Brovelli cello, Elisa La Marca theorbo/guitar

56:16

Dynamic CDS7918

Click here to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[Doing so supports the artists, the record company and keeps this site available – if no-one buys, this ad-free site will disappear…]

Paduan-born Giovanni Battista Bassani (c.1650-1716) was an almost exact contemporary of Corelli, but an infinitely more versatile composer. Believed to have studied in Venice with Legrenzi, he was not only a virtuoso violinist, but also a fine organist worthy of holding several important posts in the cities of northern Italy in which he worked, Padua, Venice, Modena, Bologna, Bergamo, but above all Ferrara, where he was maestro di cappella of the cathedral from 1686. His extensive catalogue includes at least nine operas (sadly now all lost apart from fragments), oratorios, of which there is an excellent recording (Opus 111, 2001) of his La morte delusa (Ferrara, 1696), many other sacred and secular vocal works and a substantial body of instrumental chamber works.

Bassani’s collection Affetti Canori was published as his opus 6 in Bologna in 1684. It consists of six single-movement ‘arias’ and with six cantatas in several movements that alternate arias with recitar cantando or arioso, often in a highly flexible way reminiscent of the quasi-scena episodes in the operas of composers like Cesti. It is the independent arias that often strike the listener as the more adventurous as to matters of harmony. The opening ‘Occhi amorevoli’, for example, one of the most exceptional pieces of the collection, starts with a plea of heartfelt beauty for the lady’s eyes to give succour to the poor mendicant, its supplicatory tone reinforced by chromaticism. Then comes a vivace giving the pleas greater urgency, before a return to the opening cantabile largo. And this is perhaps a good moment to introduce the singer, soprano Anna Piroli, who like the music itself excels in this work. She is the possessor of a fresh, sweet-toned voice that not only has a technique fully able to encompass agile passage work, though there is nothing over-demanding in that respect here, but also capable of sustaining an unwavering cantabile line. As can be heard in the final bars of this aria, Piroli’s mezza voce is quite ravishing, and with the very occasional exception of a pushed top note she’s one of those rare singers that seem incapable of making an unpleasant sound. Ornamentation is well-executed and mostly stylish, though it would have been good to hear an occasional trill. While her diction is fair there are times where a firmer projection of the text would not come amiss. Her response to text is however often telling; listen for example to her wistful emphasis on the words ‘goduti contenti’ (former pleasures) in one of the recitatives from the cantata Consolata gemea.

That is at once the most extended and arguably the most impressive of the cantatas, though several others come close. While most of them take the vicissitudes of love fairly light-heartedly – and the number of lively triple-time arias tells us we should not take the content too seriously – here the cantata is founded on a beautifully expressive minor-key largo that acts as a ritornello refrain – its repeats intelligently decorated – that seems to speak of something more profound. It is most affectingly sung by Piroli, who sustains the pathetic cantabile lines with especially touching effect. Also particularly noteworthy is another lengthy cantata, Ardea di due begl’occhi, with its captivating aria in chaconne form.

Piroli is given outstanding support by the continuo players, whose contribution is always positive without ever intruding onto the singer’s territory, a lesson some others would do well to take on board. It is, in fact, a compliment to say that most of the time the listener is not aware of them.

Full texts and translations plus extended notes by musicologist Marco Bizzarini are included, rounding off a thoroughly satisfying and rewarding issue that brings this splendid set of works to the catalogue for the first time.

Brian Robins