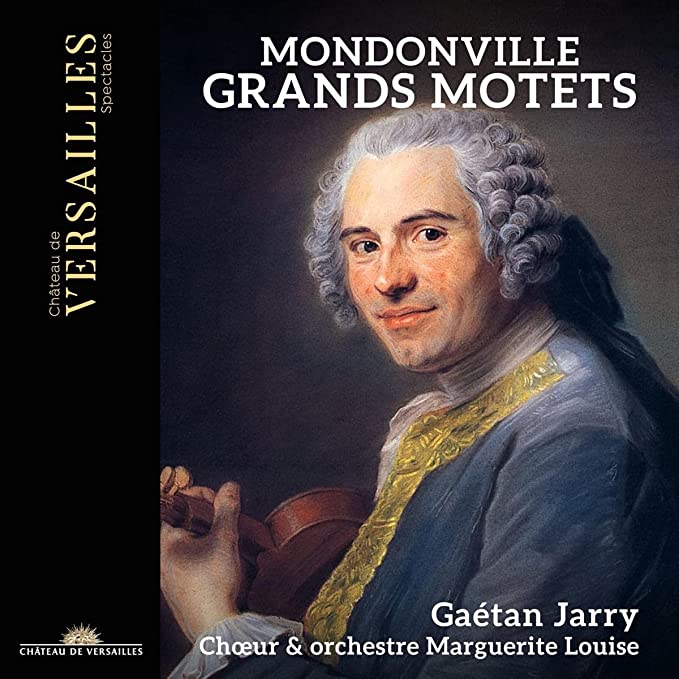

Choeur & Orchestre Marguerite Louise, directed by Gaétan Jarry

67:39

Versailles Spectacles CVS 063

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[Clicking these sponsored links keeps this reviews site free to access]

This continues the invaluable Versailles Spectacles series devoted to the grand motet, large-scale psalm settings for soloists, chorus and orchestra that were the principal form of sacred music in the France of Louis XIV and Louis XV. Those of Mondonville belong among later examples, succeeding and indeed vying in popularity with those of Rameau, whose small output was the subject of the previous release in the series, performances given by the same ensemble. My review of that outstanding CD can be found on this site.

Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville was born in 1711, a member of a poor but aristocratic Languedoc family. At the age of about twenty, he went to Paris, quickly establishing himself as a composer of instrumental music and a violinist. The cover portrait of him by Quentin de la Tour depicts an agreeable and handsome man in his late 30s whose social skills won him favour at court from the likes of Mme de Pompadour. Mondonville gained a number of posts in the Chapelle Royale, including in 1739 that of master (Intendant) and his music was so successful at the famous Concert Spirituel in Paris that he became its most frequently performed composer of all time. A number of his motets were first performed there. Although Isbé (1742), his first work for the Paris Opéra, was a failure, Mondonville’s later operas achieved considerable success, the ballet-héroique Le carnaval du Parnasse (1749) in particular opening with a run of no fewer than 27 consecutive performances.

The present recording includes three of Mondonville’s nine grands motets. Of these Dominus regnavit (a setting of Psalm 93), composed in 1734, is the earliest and indeed the first of the motets, while Coeli enarrant gloriam Dei (Psalm 19) and In exitu Israel (Psalm 115), dating from 1749 and 1753 respectively are late works that represent his final examples of the genre. Of these, In exitu is an outright masterpiece, a superbly dramatic work that fully captures the grand sweep, colourful diversity and rich harmonic texture of a text that tells of the flight from Egypt. The passages narrating the miraculous crossing of the Jordan are vividly depicted, the seething swirling river parted to the stuttering wonderment of the chorus alternating between declamatory homophony and contrapuntal writing. Perhaps even more remarkable is the succeeding haute-contre solo, later with chorus, coloured by dark bassoon sonority, ‘Montes exultaverunt’ (The mountains skipped like rams’) and following rhetorical bass solo, ‘Quid est tibi, mare …? (What aileth thee, O thou sea). Also noteworthy is the Italian influence of a passage such as the soprano ariette ‘Qui timent’ (Ye that fear the Lord). The entire work bears more than eloquent testimony to Mondonville’s mature style.

Unsurprisingly neither of the other motets quite matches this quality, though the colourful text of Psalm 93, which also speaks of floods, evokes a powerful pictorial response to ‘the surges of the sea’ and praise of the ‘voices of many waters’. Coeli enarrant, planned on a less ambitious scale, opens more conventionally, but is elevated to near transcendence in a wonderful passage that speaks of God’s creative handiwork, the setting of a ‘tabernacle for the sun, which is as a bridegroom coming out of his chamber’. There is a marvellous sense of mystery in Mondonville’s setting, a bass solo, rising from the darkest pianissimo to full glory and the restrained entry of the chorus.

I gave the highest praise to the performances of the Rameau motets by Gaétan Jarry and his supremely talented forces, praise that can be fully reiterated in the present case. On every level, this is another issue that demands to be heard by anyone remotely drawn to the music of the French Baroque.

Brian Robins