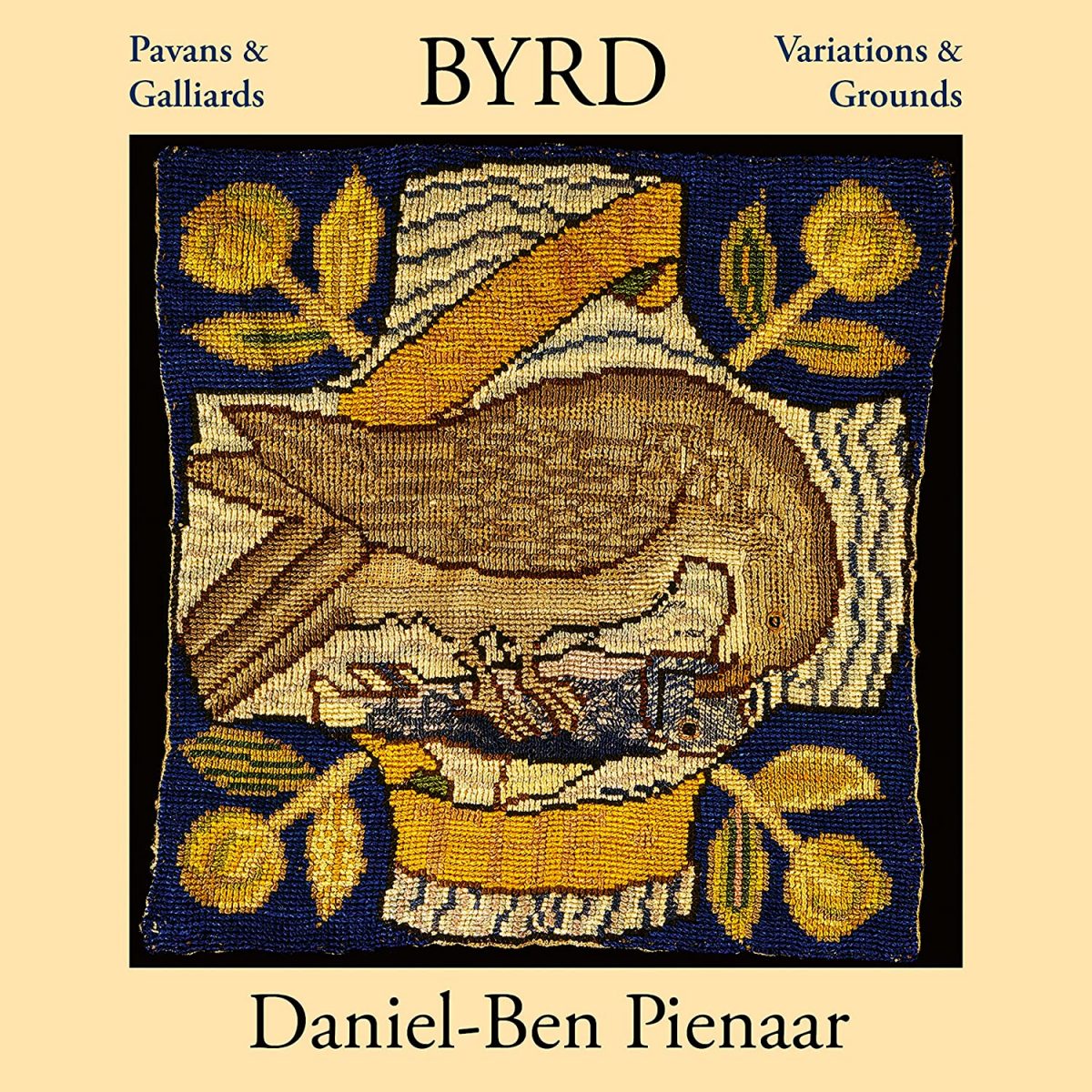

Daniel-Ben Pienaar (piano)

154:59 (2 CDs)

Avie AV2574

This is an intriguing double album: 39 of Byrd’s 101 surviving works for keyboard, composed for the contemporary harpsichord, but played here on the modern piano. The contents include all ten of the great Nevell pavans and galliards alongside the Quadran and Salisbury pavans and associated galliards, the three titled Grounds, his eight most famous settings of popular songs of the day, and three works which also qualify as grounds: The bells, Qui passe and, perhaps the only singular inclusion, the Hornpipe. Several of these pieces have been recorded by other pianists, the greatest overlaps occurring on the albums by Glenn Gould and Kit Armstrong (Sony B8725413722 and DG 486 0583 respectively; my review of the latter was published on 25 August 2021), but not forgetting Joanna MacGregor’s take on Hugh Ashton’s ground (Sound Circus SC007) and more recently Karim Said’s Qui passe (Rubicon RCD1014). Pienaar eschews the fantasias and voluntaries, plus (understandably) the works based around plainsongs which, with their many sustained notes, Byrd obviously intended (or at least preferred) to be played on the organ. So, where do these versions sit among the other substantial recordings of Byrd’s keyboard music played on the piano? What is there to be said about Pienaar’s interpretations of the pieces? And what do Pienaar’s interpretations contribute to the debate about performing these works on the modern piano, the emergence of which was still at least a century away in the future?

Playing this repertory on the piano raises a host of issues. Given the stratospheric status and quality of Byrd’s keyboard music, it is essential that it is accessible to as many people as possible. Nowadays there is a plethora of instruments based on keyboards, both traditional and electronic. To date, commercial recordings, broadcasts and public performances have been given either on the harpsichord and related instruments (hereinafter simply “harpsichord”), or the organ, or the piano. The last thing any sensitive reviewer would want to do would be to discourage performances on the piano, or to patronize pianists over their choice of instrument. While not quite an elephant in a room, the fact remains however that the music was composed for the harpsichord and/or organ, and it is at least arguable that had the piano been available to Byrd, he would have composed his pieces idiomatically to that instrument. And that matter of idiom – that a work composed for the harpsichord might not sit so well upon a different albeit similar keyboard instrument – can be a stumbling block, whether this is because the piano has a different mechanism from the harpsichord, or because a different technique is required for playing either instrument, or because it simply does not sound right to the listener. Pienaar’s recording throws up all these issues (and more – how long have you got?), which is unsurprising given the quantity and quality of the chosen music.

That chosen music is all, within the context of Byrd’s oeuvre for keyboard, familiar apart from the impressive Hornpipe of which there is only one other commercial recording – on the harpsichord – currently available (Friederike Chylek, Oehms OC1702). So, to look at that aspect from a critical perspective, we are being invited to listen to nearly forty of Byrd’s best-known pieces being played on the anachronistic piano when they are all easily accessible on recordings where they are played on the authentic harpsichord (noting that such recordings sometimes use harpsichords the designs of which postdate Byrd’s compositions). Or … we are being invited to listen to a large swathe of Byrd’s keyboard repertory played on an anachronistic but similar instrument which requires no alteration to a single note that Byrd has written, and which might, in the right hands, offer new insights into the structure and meaning of this incomparable corpus of works.

Pienaar’s performances are unapologetically those of a pianist, not of someone trying to make his instrument sound like a harpsichord. This is good in that it links Byrd with later composers for the piano such as Chopin for whom counterpoint is an important structural element, besides the rhetorical use of chordal passages (another penchant of Byrd’s, also noticeable in his vocal works, e.g. famously the A flat chord near the end of Infelix ego). This means that Pienaar can sound a bit precious in some of the pavans, but his essay in the accompanying booklet is an assertive justification for using the piano against those who show “moral outrage” at such a decision. Indeed, his rendition of Walsingham which is timed at an extraordinarily fast 6’39” (all other current versions whether on harpsichord or piano are over eight minutes, in one case nine) seems almost to be an aggressive demonstration of the capabilities of the modern piano and an exhibition of the technical capabilities of the pianist. And while this is one of Byrd’s most intense works (see for instance Bradley Brookshire’s article “’Bare ruin’d quires, where late the sweet birds sang’: covert speech in William Byrd’s ‘Walsingham’ variations”, in Walsingham in literature and culture from the Middle Ages to modernity, edited by Dominic Janes and Gary Waller, Farnham, 2010, pp. 199-216), Pienaar seems to be invoking the tune’s modest status as a popular song and, through his performance, provoking thoughts of Byrd’s passionate reaction to this place of mediaeval pilgrimage and to its destruction as a Catholic shrine by Protestants in 1538. Yet elsewhere his interpretation of O mistress mine, I must brings out all the light and sheer beauty in Byrd’s setting, making it sing in such a way as to persuade listeners that this music might actually have been composed for the piano.

So we have a choice. We can purchase the recording for what it is. We can purchase it as an experiment or a novel experience and enjoy finding out which performances work and which do not. Or we can decide that Tudor keyboard music on the piano is not for us. For this reviewer (and I did indeed buy a copy before I was invited to review it!), among some tracks that are dances that don’t (not all the Nevell pavans and galliards “take off”), or where Byrd’s momentum and polyphony are clogged by too many spread chords (ditto), or where something other than Byrd’s self-explanatory genius is being exhibited (virtuosity in John come kiss me now, another fastest version on disc), there are many performances that are decorous, thought-provoking or challenging (for instance Qui passe, The bells, and those three titled Grounds, plus the mighty Quadran pavan and galliard) and have made that purchase worthwhile. When I first encountered this repertory I had no access to a harpsichord and played through Byrd’s entire keyboard output on the family’s piano, so please, any pianists reading this review, please do play and perform Byrd’s keyboard music on your pianos, especially in this quatercentenary year.

Richard Turbet