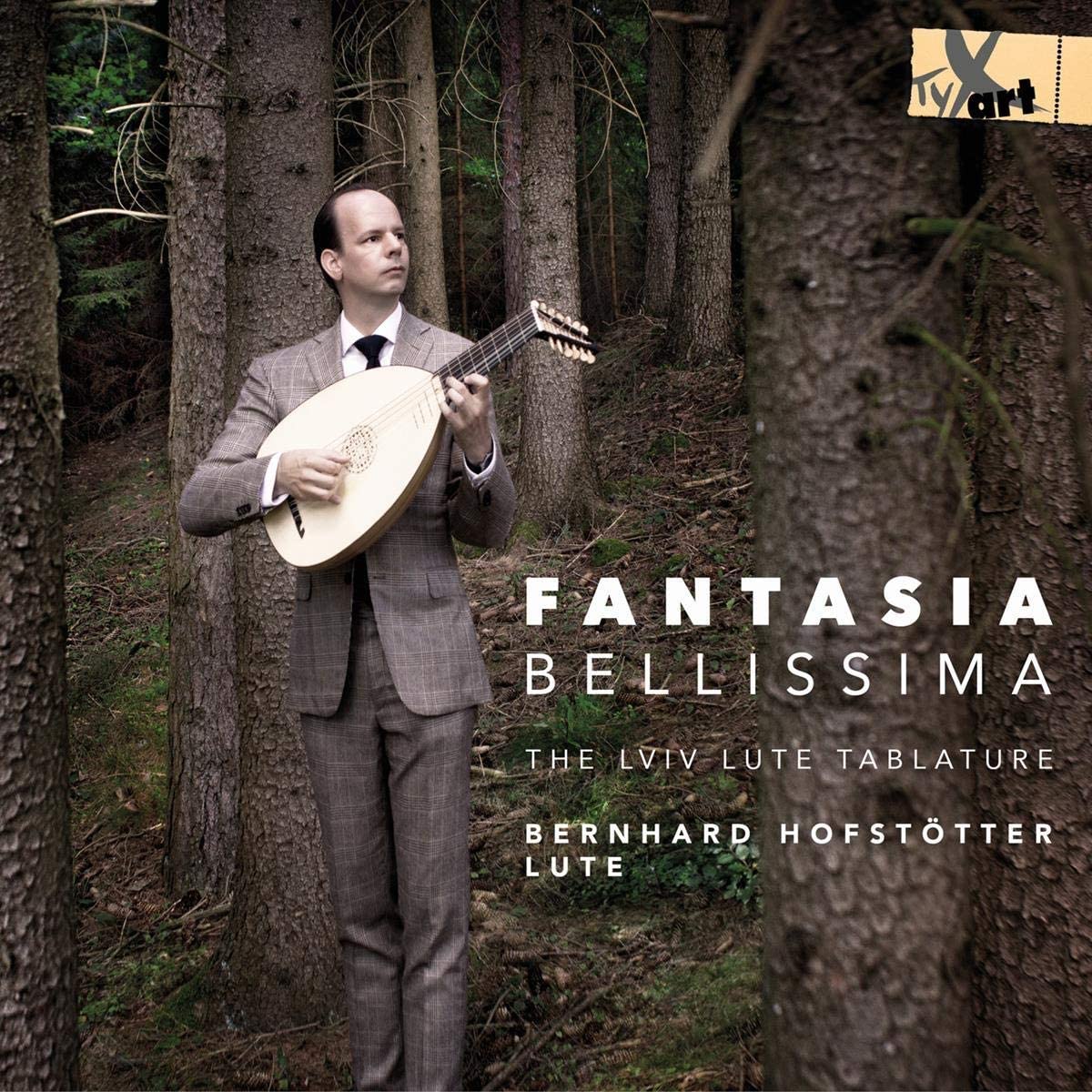

The Lviv lute tablature

Bernhard Hofstötter lute

41:51

TYXart TXA18115

To buy this recording on amazon.co.uk using a sponsored link, click HERE – this supports the artist and the label and keeps this website ad-free!

The city of Lviv, one of the main cultural centres in Ukraine, has had many names over the years, including the Polish Lwów, German Lemberg, and Russian Львов (Lvov). The University Library has in its possession a manuscript (UKR-LVu 1400/I) which contains music notated in French and Italian lute tablature. This manuscript, referred to by Bernhard Hofstötter as “The Lviv Lute Tablature”, is the source of the music for the present CD. Confusingly, in the CD liner notes Kateryna Schöning refers to the book as the “Cracow Lute Tablature”. An early owner of the book, Schwartz-An[drzej] Czarny, wrote in the manuscript that he was from Crakow, and gave the date 1555. The watermarks show that the paper was made not far from Crakow. A description of the lute music with incipts may be seen on line at – Piotr Poz´niak (Cracow), ”The Kraków Lute Tablature: A Source Analysis”, Musica Iagellonica, (2004) ISSN 1233–9679. This manuscript is not the same as “The Cracow Lute-Book”, vol. 2 of Valentin Bakfark Opera Omnia, ed. Homolya István and Dániel Benkö, (Budapest: Editio Musica Budapest, 1979), which is a modern edition of a printed source: Valentin Bakfark, Tomus Primus (Crakow, 1565).

Bernhard Hofstötter claims that his recordings of pieces from the Lviv lute book are “World Premiere Recordings”. You could argue that Oleg Timofeyev beat him to it back in May 2011 with his recording, The Lviv Lute (Sono Luminus DSL-92134) recorded on 21st May 2011, with 19 pieces from the manuscript. However, Timofeyev’s recording is with his group Sarmatica, and the music has been arranged to be sung and played by various instruments. Hofstötter plays the music, albeit with some artistic licence, as it is in the manuscript, intabulated for solo lute, so I think his claim could be justified. He plays a 7-course lute after Vendelio Venere by Renatus Lechner, which is very bright in the treble (either that or the recording engineer makes it bright).

The first and last track, “Tarzeto”, consists largely of variations over the ground IV, V, I, I. To create extra excitement Hofstötter starts strumming that chord sequence about half-way through, and speeds up towards the end. To some listeners, strumming may seem out of place for the lute, yet there are occasional examples in extant lute sources, e.g. Hans Newsidler’s “Gassen hawer” (1536). It’s a matter of taste, of course, but I would prefer not having Hofstötter’s extra excitement. I think the piece is fine as it is, and does not need turning into something resembling Gaspar Sanz’s well-known Canarios for baroque guitar. A facsimile of the music (ff. 31r-31v) may be seen on line in Piotr Poz´niak’s article cited above. There is no strumming notated in the manuscript. Hofstötter’s oft-repeated IV, V, I, I sequence actually comes only twice at the end of the piece in the manuscript, not numerous times at the beginning as he plays it. As notated, it’s a nice piece, rather like a calata by Dalza on a good day.

There are three fantasias by John Dowland in the Lviv manuscript. Track 2 is an upbeat interpretation of Fantasia no. 6 (Poulton & Lam). Hofstötter understandably looks for ways of making the music expressive – adding occasional ornaments (good), rolling chords, e.g. the second chord of bar 7 (effective in enhancing the following 7-6), easing off in bar 21 (nice, because it helps a change of mood), and bringing the music to an overdramatic stop in bar 23 (not nice, because it loses momentum). One thing I really do not like is the exaggerated séparé of four two-note chords in bars 3-4. It interrupts the flow (one of each séparé pair must by definition be out of time), and it obscures the two-part polyphony.

Hofstötter plays 19 pieces altogether. (There are twenty tracks, but Tarzeto appears twice.) Some are very short. Passo e mezo (track 11) lasts a mere 24 seconds, although it makes musical sense when followed in the next track by a matching Saltarello (52 seconds of which the last 12 seconds are silence before the next track starts). Scattered among the jolly dance pieces are some song intabulations – Claudin de Sermisy’s “Le content est riche”, Pierre Sandrin’s “Doulce memoire”, Jacquet de Berchem’s “O s’io potessi donna”, and Clément Jannequin’s “Or vien ça, vien”. Valentin Bakfark’s “Non dite mai” with its title looks like a song intabulation, but it is a galliard. A modern transcription may be found in vol. 3, pp. 51-2 of the Bakfark edition mentioned earlier.

There is much variety. Strumming returns in a setting of La rocha el fuso, but it is used sparingly – just for the fast repeated chords of one section. It is very effective, and I think appropriate here. Particularly pleasing is Hofstötter’s performance of Giovanni Pacoloni’s well-named Fantasia bellissima, which is used for the title of the CD. There is a slowly-paced rendition of Dalza’s Pavana alla Ferrarese – the tempo has to be slow if only to be able to fit in all the fast notes at cadences and elsewhere. From a later age comes Dowland’s Forlorn Hope Fancy (Poulton and Lam, no. 2) with its lugubrious descending chromatic motif. All in all, the Lviv lute tablature is an interesting source, not widely known even in the lute world. Hofstötter has done well to bring it to our attention with a lively and pleasing performance.

Stewart McCoy