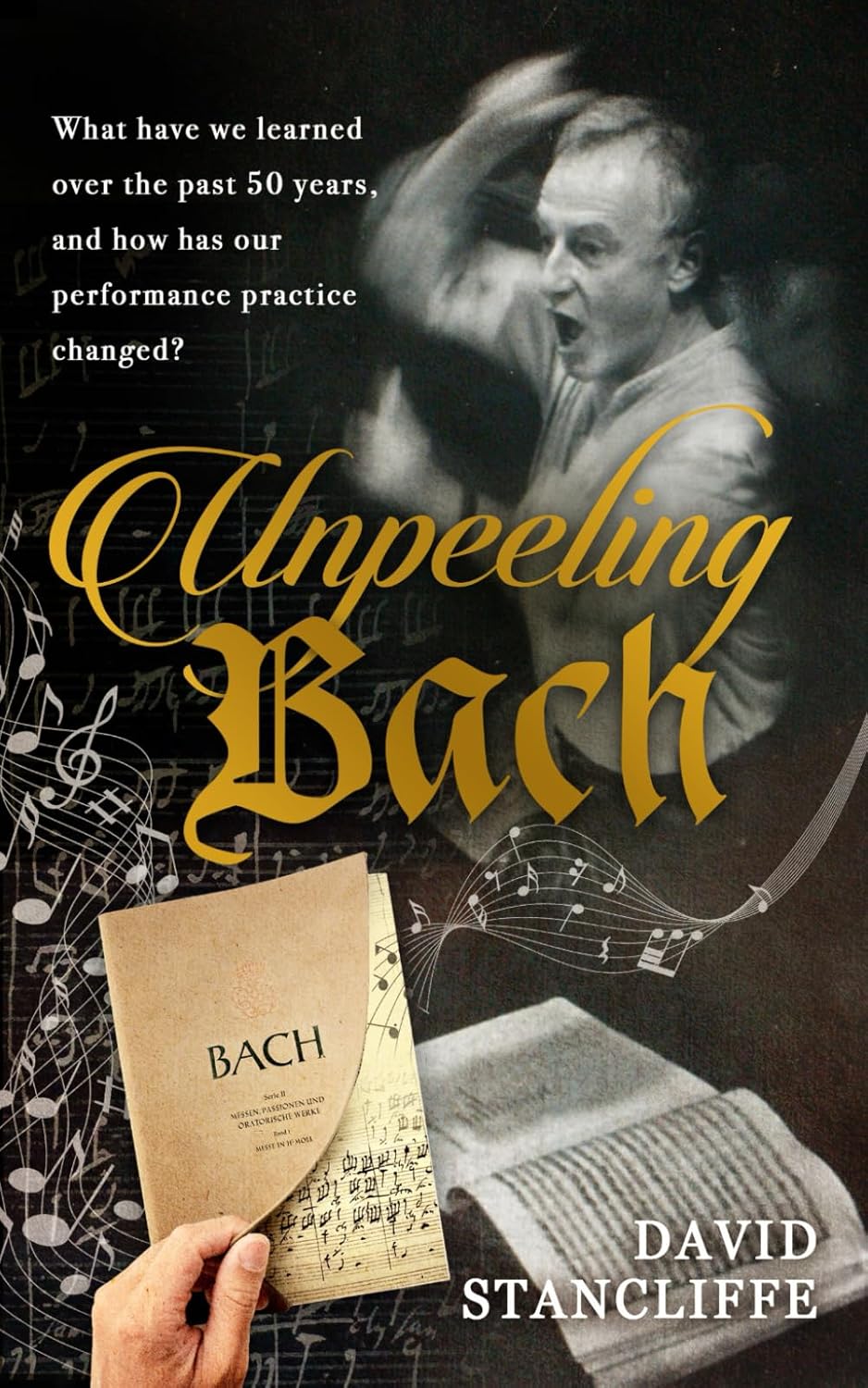

By David Stancliffe

The Real Press 2025

372pp. ISBN

Available from Amazon

This is an engaging and comprehensive study of the music of J S Bach, which places it expertly in a historical and religious context. A former Bishop of Salisbury, Stancliffe is ideally placed to consider the spiritual dimensions of Bach’s sacred music, an important aspect of this devout composer’s essence and world view which is often glossed over in other studies of his music. While this understanding pervades the whole book, we also have appendices, including one dealing with Bach’s understanding of St John’s theology, drawing on his St John Passion, which are fascinating. However, intriguing as this is, it is just one aspect of a wonderfully wide-ranging approach to Bach. We have an updated treatment of Bach’s musical context, taking into account the surprising range of earlier polyphonic music still in currency in Bach’s time. We are cleverly drawn into the issues relating to the historically informed performance of the music by an account of Stancliffe’s own journey into grappling with these issues. As a performer/director as well as a scholar, he has a rewardingly ‘hands-on’ approach to the music, extending to the most successful layout for performances as well as a detailed treatment of instrumentation, voice-types, and voice production. Again, in a very practical approach, he cites performances and recordings by leading ensembles at work right now on the music of Bach, evaluating the success of their various approaches. In this way, his reader can easily access illustrations of the points he is making, and as so often in this volume, his encyclopaedic knowledge speaks of extensive listening, which matches his voracious reading. Just occasionally, the author makes a throw-away comment which opens a thought-provoking doorway – for example, in mentioning the pair of Litui which accompany the motet O Jesu Christ, meins Lebens Licht (BWV 118), he moots the idea that the nature of their accompaniment ‘argues for at least an outdoor if not processional performance’ – intriguing! My review copy is a pre-release edition, with editorial corrections, but as these are mainly layout issues, I assume they have all been addressed in the final edition. Stancliffe’s writing style is fluent and expressive, and the structure of the book makes the material easy to access and to enjoy either by dipping in and out or simply consuming it as a good and satisfying read. Although there are regular informative quotations from contemporary sources, there are no musical examples or visual illustrations – I was initially struck by this omission, but found myself less and less aware of it as I read on. On the back of the book, David Stancliffe is described as ‘an enthusiast and expert’, and in ‘Unpeeling Bach’ we find that this is a compelling combination which gives the author a unique perspective on Bach’s music.

D. James Ross