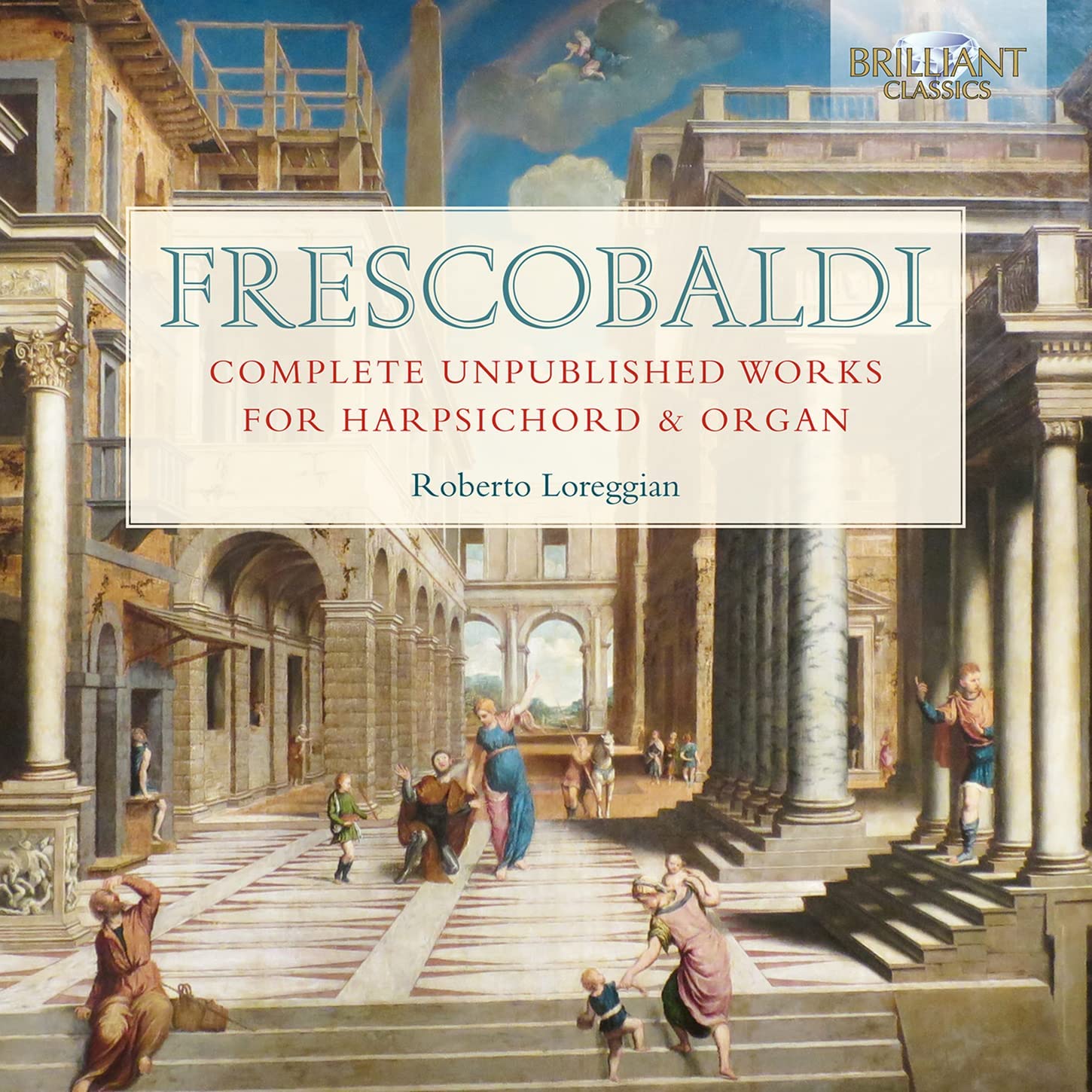

Roberto Loreggian

<TT> (6 CDs in a double CD case)

Brilliant Classics 96154

Click HERE to buy this boxed set on amazon.co.uk

[These sponsored links are your only way to support this FREE site]

This collection of six CDs marks the conclusion of Roberto Loreggian’s impressive journey through the complete keyboard music of Frescobaldi, begun back in 2008. While Frescobaldi was a careful preparer and editor of his music for publication, providing a significant canon of authentic pieces, a surprising amount survives in manuscripts scattered all round Europe. This recording has 166 pieces in total, all unpublished during the composer’s lifetime, but issued in 2017 by Etienne Darbellay and Costanze Frey as the final part of their complete edition for Suvini Zerboni. Only a handful are thought to be in Frescobaldi’s hand, but many have been identified as in the hands of collaborators and pupils such as Nicolò Borbone and Leonardo Castellani. Some are substantial pieces; others are short sketches, trial runs for later published pieces, teaching exercises, etc. Authenticating them is a complex business and has occupied scholars over many years, most notably Claudio Annibaldi, Etienne Darbellay, Frederick Hammond, Christine Jeanneret and Alexander Silbiger. Discussion continues about many pieces, and some at least are more likely to be by Frescobaldi’s pupils or followers. Silbiger maintains an online catalogue (Frescobaldi Thematic Catalogue Online (sscm-jscm.org)), hosted by the Journal of Seventeenth Century Music. He has attached F numbers to all pieces attributed to Frescobaldi, published and unpublished, thought to have at least the potential of having been composed by him; for the most part, these F numbers are attached to pieces in Loreggian’s recording, though some have been missed out. Hammond hosts an annotated catalogue of all sources on his website (Girolamo Frescobaldi: An Extended Biography – Frederick Hammond, Bard College), using Silbiger’s F numbers. Between them, these two websites provide the information necessary to contextualise Loreggian’s achievement; the liner notes provide only basic information about the sources.

For those already familiar with the works of Frescobaldi, listening to this recording is at once a disorientating and stimulating experience. Much of the language is familiar and sometimes whole sections are recognisable, but pieces are curtailed, go off in different directions, or use the basic building blocks in an altered way. It is fun speculating whether this or that piece is really by the composer. Above all, the recording provides a crucial insight into the workshop of Frescobaldi, his pupils and followers, and the raw material from which his published pieces emerged fully varnished. There are few surprises here: all the standard genres are found, with lots of random dance movements in particular. There are also sets of partite on familiar themes as well as canzonas, ricercars and toccatas. Some of these last are thought to be late works by Frescobaldi, but might also be by his pupils: they are certainly very accomplished. In particular, a set of three toccatas copied by the musician and engraver Nicolò Borbone in Ms. Chigi Q IV 25, and eleven canzonas also copied by Borbone and now in British Library Add. Ms. 40080, are well worth listening to. There are plenty of other gems too. At the other end of the scale, some pieces are extremely cursory, lasting less than a minute in some cases. Pieces seem to have been ordered by choice of instrument, rather than according to any particular criteria, with no attempt to single out the exceptional from the merely ordinary.

Loreggian has done a very impressive job, taking the pieces equally seriously, and giving them all the same level of attention. He plays on two organs: that built in 1565 by Graziadio Antegnati for the Cappella Palatina in Mantua’s Ducal Palace, and one made by Zanin Organi in 1998 for the Chiesa di S. Caterina in Treviso. He also plays on two modern copies of 17th-century Italian harpsichords by F. Gazzola and L. Patella. All work very well for their chosen pieces and are sensitively registered; recording quality is excellent throughout. There is one surprise in the registration, but I won’t spoil the fun by revealing it! Loreggian has a real gift for making the music sound as if he is improvising it – it is easy to imagine Frescobaldi himself in the room with the listener. As a performer, he is steeped in the musical language of the period and responds with great fluency to the changing declamatory rhythms and affective figures so typical of the composer and his milieu. He is to be congratulated for making all of this music, warts and all, available to listeners. This is a collection to dip into repeatedly for rewarding insights and is a very welcome addition to Frescobaldi discography.

Noel O’Regan