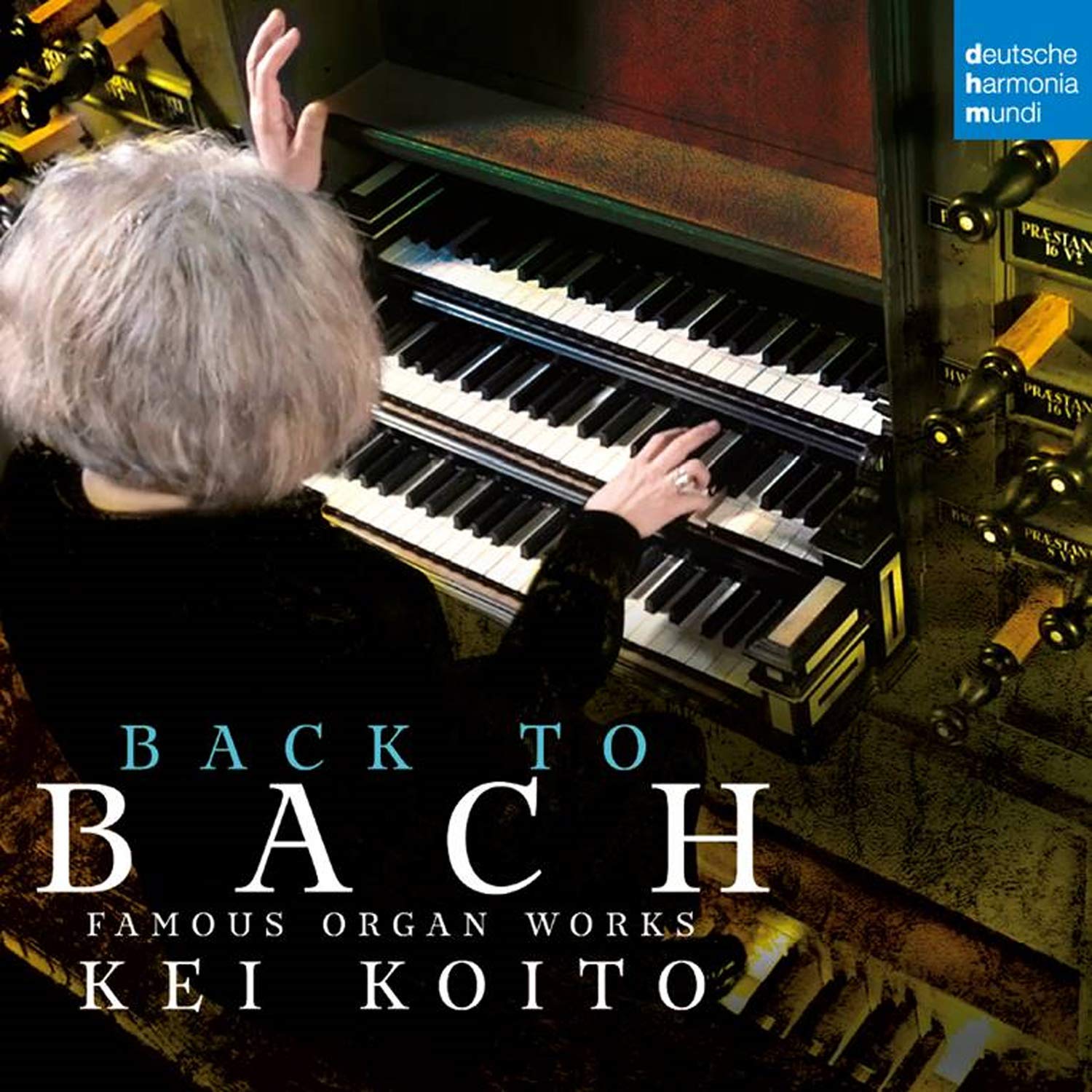

Famous Organ Works

Kei Koito (Arp Schnitger Organ (1691/92, Martinikerk, Groningen)

70:45

deutsche harmonia mundi 1 90759 15582 0

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

This is the next CD in the series of recordings released by Kei Koito on finely conserved period organs. This time it is the turn of the Arp Schnitger organ in the Martinikirk in Groningen in the Netherlands. The booklet has the organ’s specification, but you need to download the registration chosen for each work from Koito’s website. This is a small inconvenience for something that not only enhances the listener’s experience of the works played but gives an insight into the kind of tone-colours available of one of the most spectacular surviving organs of the period.

The instrument has a complex history: a gothic organ of 1450 was altered in 1482, and then altered in Renaissance style in 1542, added to in 1564 and 1627-8, altered in 1685-90, then substantially rebuilt and enlarged with enormous 32’ Principal pedal towers by Arp Schnitger in 1691-2 after various disasters. In 1728-30 it was given a new Rugpositief by Schnitger’s son and Hinz, and again repaired and enlarged by Hinz in 1740 after subsidence. Then between 1808 and 1939, when the action was electrified, it was altered and substantially re-voiced, so that the historic origins of the organ became scarcely discernable. A major work of restoration was then executed over more than an eight-year period between 1976 and 1984 by Jürgen Ahrend to bring it back to its supposed 1740 shape and sound, with the advice of Cornelius Edskes. The result is very fine, but it has none of those slight variations between notes that make many organs surviving in more or less their original form so melodically fluent, and is a characteristic of – for example – a careful reproduction of a 1720s Denner oboe.

I have not had the opportunity to examine the organ in detail myself, but the photographs on the website make it clear that the frame and action are entirely new and much of the pipework has been re-voiced (again). Of the 53 stops, 20 are in origin Schnitger or earlier, 14 are from the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries and 19 are entirely new.

Koito plays a good mixture of pieces opening with the Dorian Toccata and Fugue (BVW 538) and finishing with that in D major (BWV 532). In the middle there is the early G minor Prelude and Fugue (BWV 535) and the G major (BWV 550). Among the interesting other pieces are the trio on Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan – only recently added to the canon – and the trio on Wo gehest du hin after Cantata 166ii, while there are choral preludes on An Wasserflüßen Babylon (BWV 653), Nun danket alle Gott (BWV 657), Komm Gott Schöpfer Heilige Geist (BWV 667), O Lamm Gottes unschuldig (BWV 656) and Herzlich tut mich verlangen (BWV 727). Two Fantasias complete the programme – super Jesu, meine Freude (BWV 713a, 1&2) and Ein fest Burg ist unser Gott (BWV 720) with the rare hints in the autograph for registration. Together they make a varied recital and show off the organ splendidly. As with her previous CDs, the playing is neat and the recording excellent.

As far as her playing is concerned, Koito can be utterly focussed on the rhythmic clarity like in the Dorian Toccata and Fugue, or very subtle – listen to how she phrases the opening of the fugue in the G major (BWV 550), where later she negotiates the tricky passagework in measures 140-143 without missing a trick. And the registration with the Hinz Hobo of 1740 and its tremulant in BWV 584 contrasts elegantly with the opening of the Fantasia super Jesu, meine Freude, where the 2’ Octaaf on the pedal for the choral balances the Rugpositief 4’ Speelfluit beautifully. And the build-up through the verses of O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig (BWV 656) is beautifully registered, and the shading possible on an organ like this with seven manual and five pedal reeds allows for an almost infinite variety of tone as well as subtle changes in volume.

One other feature that makes this such a good recording is of course the acoustic and the way this is handled by the recording engineer. When I first heard the surviving organs in the Netherlands in the late 1950s, I was astonished at the reverberation in many of the churches and wondered at the clarity that seemed to be possible. The amazing blendability of numerous ranks of upperwork, voiced on what seemed then to be astonishingly low wind pressure, seemed to be a gift of many of the barn-like buildings and so very unlike the screaming upperwork that the advanced classical merchants were pedalling as “Baroque” in England. These days we are lucky to have creative artists working painstakingly at the conservation of these extraordinary survivals, and the Martinikerk organ in Groningen has no fewer than nine known organ builders responsible for the instrument over the years, even if we think of it mainly as the creation of Arp Schnitger. Would it sound so stunning if it were relocated to a dry concert hall acoustic?

David Stancliffe

We have received a second review of this disc.

Don’t be put off by the populist title of this CD. Although some of its contents are well known, there are less famous pieces too and the whole makes a highly satisfactory recital on the historic organ in Groningen’s Martinikerk, one of the largest survivals of the baroque period. Dating originally from the 15th century – and retaining some of those pipes – it was rebuilt many times, most famously by Arp Schnitger and his son in the period 1692-1729. Subsequently neglected, it was restored to its 1740 state by Jürgen Ahrend in the early 1980s and is once again a splendid instrument. Koito is not phased by its history, or its size, and produces a varied palette of registrations which shows it off to advantage, helped by the sound engineers who have successfully dealt with the challenge of reproducing it with both resonance and clarity. She plays four big Preludes/Toccatas and Fugues (including the Dorian), two Fantasias and five Chorale Preludes, plus a couple of charming Trios. I particularly enjoyed An Wasserflüssen Babylon BWV 653 which showcases a beautiful sesquialtera and a flute, and the Fantasia on Ein feste Burg BWV 720 which exploits the reeds. The big pieces on full organ are impressive too, especially the final Buxtehudian Prelude and Fugue BWV 532. Tiner notes are informative about the music though, strangely, not about the organ. Indeed, one has to search quite hard to find a mention of the instrument at all, only in very small print on the back cover, which seems odd given its importance. We are directed to Koito’s own website for further information and reflections, including a full list of registrations for each piece. Overall, this is a very satisfying recording.

Noel O’Regan