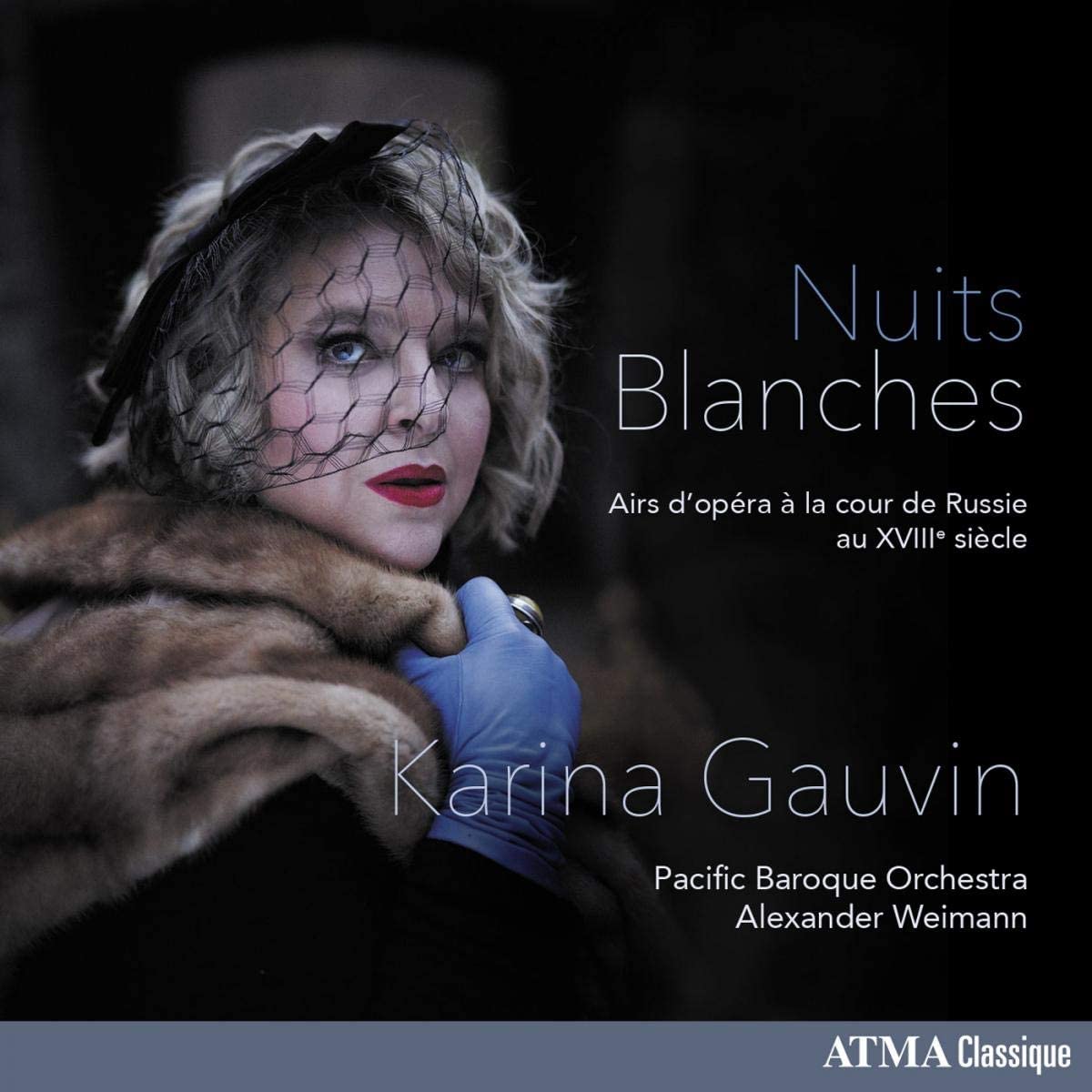

Airs d’opéra à la cour de Russie au XVIIIe siècle

Karina Gauvin, Pacific Baroque Orchestra, Alexander Weimann

TT? ca. 58:00?

Atma Classique ACD2 2791

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Although subtitled (in French) ‘Arias from the 18th-century Russian court’, the CD under consideration, in fact, includes little with a direct connection to the court, in contrast to Cecilia Bartoli’s ‘St Petersburg’ (Decca). That included music by Francesco Araia (1709-c.1770), who can be considered the father of opera in Russia, and Hermann Raupach (1728-1778), the father of Russian language opera. Neither feature on the present not-so-generously-filled disc, the greater part of which is devoted to extracts of operas first given in Italy by the Ukrainian-born composers, Maxime Berezovski (1745-1777) and Dimitri Bortnianski (1751-1825), and Gluck, extracts from whose Armide are included for the tenuous reason that Berlioz introduced it to Russia, long after the death of its composer.

Berezovski’s credentials as an ‘Italian’ opera composer are impeccable. In 1766 he was sent at the expense of the Russian court to Bologna study under Mozart’s mentor, Padre Martini, being awarded the diploma of the famed Accademia Filarmonica. His Italian sojourn concluded with a successful production of his opera Demofoonte in Livorno in Carnival 1773. Today only four arias survive, two of which are performed here by Canadian soprano Karina Gauvin. Particularly impressive is ‘Misero pargoletto’, sung by the Thracian prince Timante as he reflects on a letter that appears to prove that his young son was unsuspectingly born of an incestuous relationship (he wasn’t, of course). Set in contrasting moods of reflective horror and dramatic exclamation, the aria makes interesting use of da capo form.

That the name of Bortnianski is rather better known is accounted for by his splendid a cappella church music, mostly composed during the period of his tenure as director of the imperial chapel choir. Prior to that, his career followed a similar trajectory to that of Berezovski. In 1769 he followed his compatriot to Italy, where he may have studied with Galuppi, who had only recently himself returned from a highly successful period in St Petersburg. While in Italy Bortnianski composed three drammi per musica, of which three extracts from Alcide (Venice, 1778) are given here. The first is an aria in which the young Alcide (Hercules) having been led to a crossroads at which he must choose between the difficult, rocky route of virtue and the easy track of pleasure is torn between the two, the aria effectively dramatising the conflict, a long accompanied recitative that brings more agonising over the choice that must be made. Finally comes a gracious lyrical andante in which Hercules expresses his thanks to the gods for guiding him on the right path, which is of course virtue. The story will be familiar to many readers from settings by Bach and Handel. All three extracts, pleasing if not especially memorable, testify to a thorough assimilation of the Neapolitan style then dominating European music. Le faucon is a later work, one of three opéras comiques composed for Crown Prince Paul, into whose service Bortnianski entered after his return from Italy. Despite the genre and language, the gracefully flowing and felicitously orchestrated through-composed aria ‘Ne me parlez point’ remains thoroughly Italianate in style. The brief orchestral pieces by Domenico Dall’Oglio and Fomine are unremarkable.

All this music is very well sung by Karina Gauvin, whose lustrous full-bodied soprano here seems in better shape than when I last heard her live. She is particularly suited to the role of Gluck’s Armide, the extracts including the big scenas ‘Enfin, il est en mon puissance’ and the end of the opera ‘Le perfide Renaud me fuit’. The latter is built to a powerful climax, well supported by the Vancouver-based Pacific Baroque Orchestra, admirable throughout under the direction of Alexander Weimann, who contributes a rather tinkly-sounding fortepiano continuo. Even if it doesn’t quite do what it says on the tin, this is an enjoyable disc that will certainly appeal to admirers of the singer and anyone interested in exploring the outer boundaries of 18th-century opera.

Brian Robins