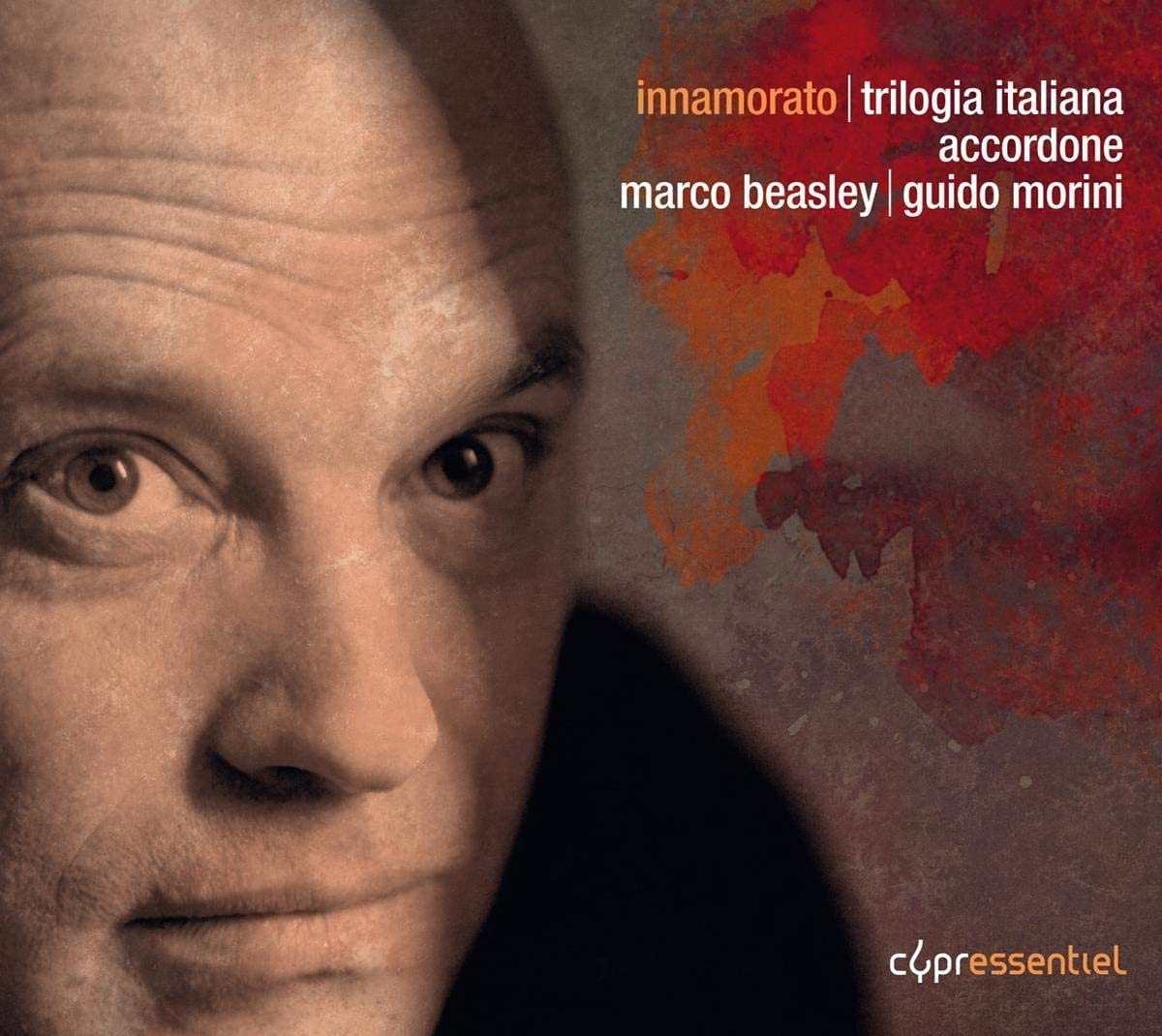

accordone, macro beasley, guido morini

188:54 (3 CDs in a card folder)

cypres CYP9620

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

For this collection of Italian music from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Accordone have selected three recordings from their back-catalogue dating from 2005, 2006 and 2007. It has to be said that the rigour of the background scholarship and the spontaneity of the performances mean that these have not dated at all. The initial disc focuses on Frottole, and is a delightfully engaging journey through the 16th century, bringing familiar composers such as Lassus and Tromboncino together with a host of less familiar names, such as Marco Cara, Pietro Paolo Borrono and Guglielmo il Giuggiola. This unearthing of unknown music by unknown composers is one of the main strengths of all three CDs, as indeed is the distinctive voice of Marco Beasley. His pleasing tenor is a major factor in the appeal of all three CDs – it is an individual sound, with a similar texture to the voice of Nigel Rogers and equally adept at sparkling ornamentation. In the Frottole volume, the ensemble manages a wonderfully spontaneous sound, verging on the performance style more often associated with traditional music. This proves ideal for the no-nonsense directness and beguiling charm of these Frottole. In the second CD Recitar Cantando we encounter repertoire for solo voice and continuo with obbligato instruments again by familiar names such as Monteverdi, Frescobaldi and Caccini and unfamiliar contemporaries such as Cherubino Busatti along with instrumental music by Giovan Battista Fontana. The slightly elusive programme note for this CD doesn’t detract from the delight of the performances, although a more detailed account of how and why the performers felt free to adapt the messenger scene from Monteverdi’s Orfeo and his dramatic madrigal Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda for solo voice and small consort would have been helpful and interesting. Just occasionally, as in Il Combattimento (which is by far the most substantial piece on the CD), Beasley, who has to sing all three characters himself, doesn’t quite imbue the vocal lines with the drama they seem to demand – there is a reference in the programme note to letting the character sing rather than the performer. This seems to be a little lacking here. For the third CD Il Settecento Napoletano we visit the musical hot-spot of 18th-century Naples. In a city where we now know opera was a major focus of attention, it is no surprise that solo secular cantatas were also very popular. It seems to my ear that these performances of ‘cantatas in the Neapolitan language’ are sung in a distinctive Neapolitan dialect, and again while Alessandro Scarlatti and Nicola Matteis (who supplies a trio sonata) are relatively familiar, Giuseppe Porcile, Giulio Cesare Rubino, Alonso dei Liguori and Guido Morini are new to me. As in all three CDs, it is interesting how the music by the ‘unknowns’ is invariably every bit as effective as that by the big names. These attractive pieces are greatly enhanced by the imaginative scoring of the accompaniments, while vocalist Marco Beasley seems more in tune with this later idiom. This is an enjoyable collection of CDs currently otherwise unavailable and definitely to be recommended for their underlying intellectual rigour and the musicality of their performances.

D. James Ross