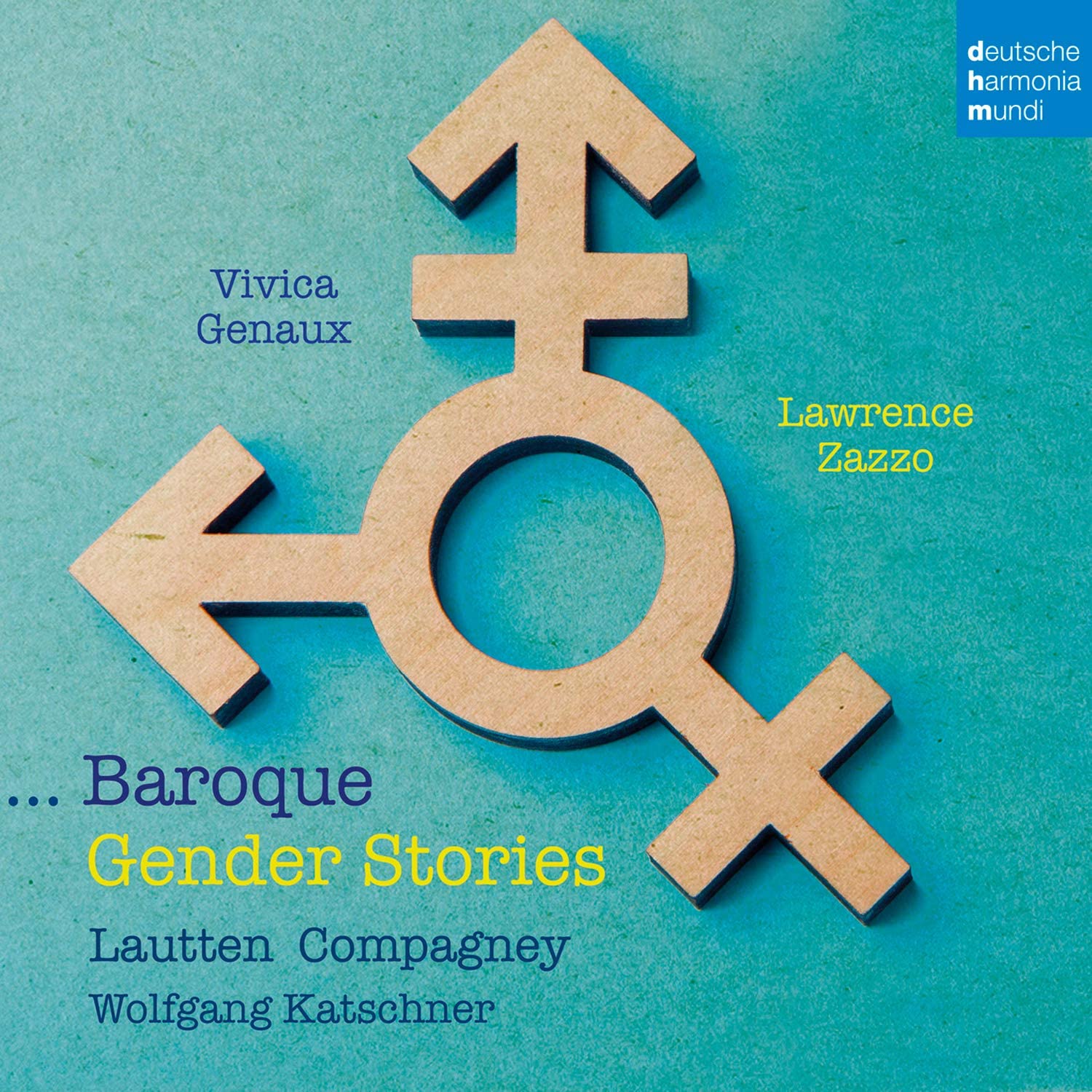

Vivica Genaux, Lawrence Zazzo, Lautten Compagney, Wolfgang Kratschner

87:25 (2 CDs in a single jewel case)

deutsche harmonia mundi 1 90759 43092 7

Music by Galuppi, Handel, Hasse, Lampugnani, Porpora, Traetta & Wagenseil

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Look beyond the bizarre title and there’s an interesting concept here. The programme consists of arias and duets that feature gender fluidity (or ‘bending’ to use the fashionable word) in one some form or another. We’re of course familiar with the use of mezzos in the great male roles once undertaken by castratos, but perhaps less familiar is the fact that female roles were also sung by castratos. This applied particularly in Rome, for the simple reason that during the greater part of the history of opera during the Baroque era papal decree made it impossible for women to appear on the Roman stage. It is just such an opera, Galuppi’s setting of Metastasio’s Siroe (1726), first given in Rome in 1754, with the noted castrato Giovanni Belardi in the role of the prima donna Emira that forms a fascinating Leitmotif for the set. And it is here, too, the playing with gender starts, since the act 3 cavatina for Emira (an insert into Metastasio’s text) is sung by Vivica Genaux, not as one might have expected Zazzo, although in the splendid duet, another insert, it is Lawrence Zazzo who sings Emira and Genaux Siroe.

In addition to the Galuppi, there are further settings of Emira’s cavatina, each to a different text, by Wagenseil, whose Siroe was produced in Vienna in 1748 and by Traetta, whose version for Munich dates from 1767. In both the Emira was more obviously sung by a woman, in the case of the Traetta the great Regina Mingotti. Here the piece, an aria de furia directed at the heroine’s father, is sung by Zazzo in the case of the rather tame Wegenseil, Genaux definitely winning out with the magnificent ‘Che furia, che mostro’, a dark, chromatically inflected tour de force splendidly delivered by the mezzo.

There are also extracts from the Siroes of Hasse and Handel, both of whose overtures are included, while another Metastasio libretto, that for Semiramide riconosciuta, provides the foundation for two settings by Giovanni Lampugnani, for Rome in 1741 and Milan in 1762, and Porpora’s outstanding 1739 version for Naples. That is here represented by the enchanting siciliano, ‘Il pastor se torna aprile’, sung with elegant charm by Genaux. Lampugnani’s Roman version obviously featured another castrato in the role of the heroine Tamiri, the flowing ‘Tu mi disprezzi’ here represented by Zazzo, whose singing throughout the programme is thoroughly musical but lacking clear individuality. His lack of a trill is particularly disappointing, as is the ornamentation in da capos by both artists, who display a tendency to vary the vocal line at the expence of adding embellishments. It’s a solution to varying the repeat that has its adherents, though unsupported by contemporary practice and here leads to some wayward control in some of the more flamboyant gestures, particularly in the case of Zazzo, whose tone is apt to become hooty in the upper register. Genaux is better in this respect and also produces some dazzling coloratura and precisely articulated passaggi, Orlando’s ‘Nel profondo’ from Vivaldi’s Orlando furioso (1727) being an especially striking example.

The support given by the Lautten Compagney is capable, if at times somewhat mannered in currently fashionable style. The very fast tempo set for Serse’s ‘Se bramate’ (from Handel’s eponymous opera) – sung by Genaux – is, for example, cast into exaggerated relief by the self-conscious slowing down at the qualifying words ‘ma come non so’ (but know not how). Elsewhere one notes the intrusive plucking from a band that true to its name includes no fewer than four (!) continuo lute players, including director Wolfgang Katschner. This at the expense of just two cellos and a single double-bass, it still having not registered in most early music circles that 18th-century opera orchestras in all the major Italian houses employed a numerous bass section.

The notes include an interesting Q and A with the two singers answering rather pretentious questions worded along the lines of, ‘Some theorists would say that gender is performative, thus only realised when we enact socially-coded behaviours for an audience …’ and so forth. Fortunately the singers’ answers are less convoluted and indeed provide plenty of food for thought. I’m still not sure Genaux’s use of the word androgynous in this context is the right term and there is arguably too much post-Freudian psychology at play; the era was far less concerned with gender definition than we are today. Notwithstanding, the set takes an unusually imaginative approach both as to concept and planning in addition to introducing some worthwhile and rarely heard repertoire.

Brian Robins